Alabama, with its rich mosaic of rivers, wetlands, forests, and coastal plains, has long served as a haven for birds—both resident and migratory. Its location within the southeastern United States places it at a crucial ecological crossroad, where northern and southern avifauna converge. However, despite its natural wealth, Alabama’s landscapes have not been immune to the sweeping environmental changes brought by human development. Logging, agriculture, hunting, and urban expansion have left lasting marks on bird populations, pushing some species to the brink—and beyond. Among these are four bird species that once graced the skies and forests of Alabama but have now vanished completely. Understanding the stories behind their extinction is not merely a retrospective exercise; it offers insight into the ecological pressures that still threaten avian life today.

1.Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius)

An Abundant Species That Once Dominated the Skies

The Passenger Pigeon stands as one of the most tragic and well-known cases of human-caused extinction in North American history. In the 19th century, this species was among the most abundant birds on the planet, with a population estimated in the billions. Their flocks were so immense and densely packed that they could block out sunlight for hours as they passed overhead during migration. Alabama lay along several of their major migratory routes, and the state’s forests—rich in oak and beech trees—provided essential food sources such as acorns and beechnuts.

Communal Behavior That Became a Fatal Vulnerability

Passenger Pigeons were highly social birds. They nested in enormous colonies that stretched for miles, with thousands of birds roosting and breeding in close proximity. While this communal behavior had evolved as a defense against natural predators, it made them extremely vulnerable to human exploitation. In the 1800s, as settlers expanded westward, commercial hunters began targeting these large colonies on an industrial scale. Pigeons were shot by the thousands, trapped in nets, and smoked out of trees. The meat was shipped by the ton to cities to feed both humans and livestock. With no laws to limit hunting or protect breeding areas, entire colonies could be wiped out in just a few days.

The Role of Habitat Loss in Accelerating Decline

In addition to overhunting, widespread deforestation across the eastern United States—including in Alabama—destroyed large swaths of the pigeons’ natural habitat. Food supplies dwindled, and nesting areas disappeared. The combination of heavy exploitation and rapid habitat loss created a cascade of ecological pressures that the species could not withstand.

A Missed Opportunity for Conservation

Although naturalists like John James Audubon raised early concerns about their rapid decline, their warnings went unheeded. By the late 1800s, Passenger Pigeons had become rare. The last confirmed wild individual was shot in 1901, and in 1914, the last known bird—a female named Martha—died in captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo. Her death marked the final chapter in the collapse of a species that had once seemed limitless. The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon remains a powerful example of how even the most numerous species can vanish within a human lifetime without effective conservation measures.

2.Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis)

A Bright and Distinctive Native Parrot

The Carolina Parakeet was the only parrot species native to the eastern United States, making its extinction especially significant in terms of biodiversity loss. These birds were striking in appearance, with vivid green bodies, bright yellow heads, and orange faces. Their noisy flocks were once a familiar sight in the bottomland hardwood forests and winding river valleys of Alabama, where they thrived in the warm, humid environment. As cavity nesters, they often chose hollow trees near water for shelter and reproduction, while their diet included a variety of seeds and fruits, including cockleburs—plants that are toxic to most animals but easily digested by this resilient species.

Social Intelligence That Backfired

Carolina Parakeets were highly social and intelligent birds, forming tight-knit flocks with strong group cohesion. Ironically, this social intelligence contributed to their vulnerability. When members of a flock were killed by hunters, surviving birds would often return to the scene, appearing to mourn their dead. This behavior, observed in other intelligent bird families like corvids, allowed hunters to kill many individuals in succession. Their bright plumage also made them easy targets in open areas, and their predictable return to familiar nesting sites further exposed them to exploitation.

Human Persecution and Misunderstanding

While they were sometimes hunted for food, Carolina Parakeets were more commonly killed for their feathers, which were highly prized in the millinery trade, especially during the late 1800s. Women’s fashion at the time often included elaborate hats decorated with colorful bird feathers, and the parakeet’s vibrant colors made it particularly desirable. Farmers also contributed to their decline, viewing them as pests due to their tendency to feed on orchard fruits and cultivated grain. With no wildlife protection laws in place, there were no barriers to mass killings, whether motivated by profit or agricultural defense.

Habitat Loss and the Absence of Conservation

In addition to direct persecution, the loss of habitat played a major role in the species’ decline. As forests along rivers and wetlands in the southeastern United States were cleared for agriculture and logging, the Carolina Parakeet lost access to essential nesting sites and food sources. Though sightings in Alabama continued into the early 20th century, their population had already been drastically reduced. The last confirmed wild sighting occurred in Florida around 1904, and by the 1930s, the species was declared extinct. Unlike the Passenger Pigeon, whose demise sparked public outrage, the Carolina Parakeet faded away with relatively little attention. This lack of action can be attributed to limited scientific understanding of avian ecology at the time, as well as a broader disregard for species considered “inconvenient” or economically insignificant.

3.Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis)

A Giant Among Woodpeckers

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker was one of the largest woodpeckers in the world, nearly the size of a crow, and among the most iconic birds of the southeastern United States. Its striking appearance—with glossy black feathers, a bold white trailing edge on the wings, and a prominent ivory-colored bill—made it unmistakable in flight. Its loud, trumpet-like call once echoed through the swampy bottomland hardwood forests that stretched across the Deep South, including southern Alabama. This bird became emblematic of America’s wild and unexplored wetlands, symbolizing the biodiversity hidden within vast tracts of old-growth forest.

Ecological Specialization and Habitat Dependence

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker was highly specialized in its ecological needs. It relied almost exclusively on large expanses of undisturbed old-growth forests dominated by tree species such as sweetgum, tupelo, and bald cypress. These trees supported the dead and dying wood necessary for the bird to forage on wood-boring beetle larvae, which made up the bulk of its diet. Unlike more adaptable woodpeckers, it did not readily shift to fragmented habitats or secondary growth. Its nesting behavior was also tied to large trees, where it excavated deep cavities far above ground level. This strict dependence on a specific forest structure made the Ivory-billed Woodpecker especially vulnerable to environmental change.

The Rapid Loss of Habitat in the American South

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the expansion of industrial-scale logging devastated the very forests the Ivory-billed Woodpecker needed to survive. Bottomland hardwood forests across the southeastern U.S., including those in Alabama, were logged at a massive scale, often leaving no large trees standing. The systematic removal of mature forests not only destroyed nesting and foraging areas but also fragmented the landscape, isolating any remaining individuals. By the time early ornithologists and conservationists began raising alarms, the damage had already been done. The once-abundant bird had become a rare sight, even in areas where it had previously thrived.

Uncertainty, Hope, and the Shadow of Extinction

Despite no confirmed sightings since the mid-20th century, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker continues to spark debate among ornithologists and birdwatchers. Unverified reports have occasionally emerged from remote swamps in Arkansas, Louisiana, and the Florida Panhandle, leading to hopeful but inconclusive searches. Technological efforts—including audio recordings and camera traps—have failed to produce irrefutable evidence of the bird’s survival. In 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service formally proposed listing the Ivory-billed Woodpecker as extinct, though the final ruling has been met with skepticism from some researchers who believe undiscovered individuals may persist in inaccessible habitats.

A Symbol of Ecological Fragility

Whether definitively extinct or not, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker remains a powerful symbol of what is lost when habitat destruction outpaces conservation. Its decline illustrates the peril faced by ecological specialists—species that depend on narrow environmental conditions and cannot adapt quickly to change. The story of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker serves as a cautionary tale: that the disappearance of complex, ancient ecosystems can trigger the quiet vanishing of even the most charismatic species. In Alabama and beyond, its memory is a reminder of the delicate balance required to sustain biodiversity in a rapidly developing world.

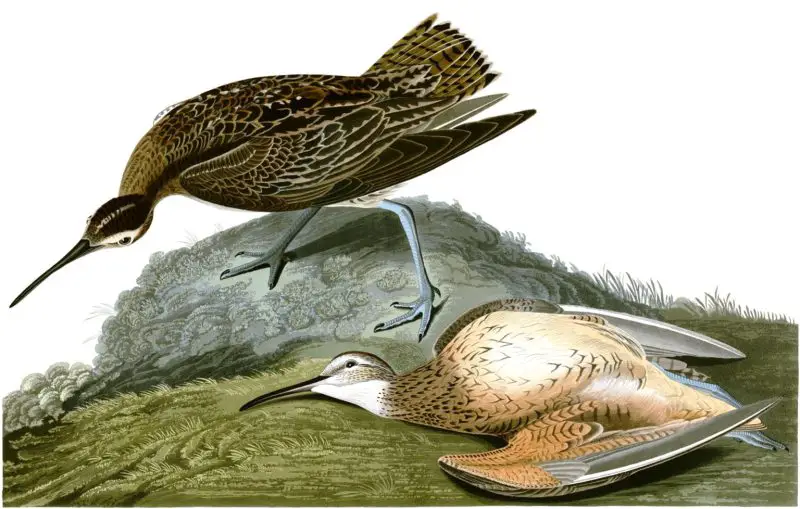

4. Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis)

A Migratory Visitor to Alabama’s Shores

The Eskimo Curlew was not a permanent resident of Alabama, but it once played an important role as a seasonal traveler through the state’s coastal and inland habitats. This slender, long-billed shorebird bred in the open tundra of the Canadian Arctic and spent the winter months as far south as Argentina. Alabama, situated along its migratory corridor, provided critical stopover sites during spring migration. Open fields, wet meadows, and coastal plains offered abundant food sources, including berries, insects, and soft-bodied invertebrates needed to fuel its transcontinental journey. During the 19th century, the species migrated through central and eastern North America in immense flocks, temporarily enriching the ecological fabric of places like Alabama.

Victim of Market Hunting and Unregulated Harvest

Despite their incredible mobility, Eskimo Curlews were highly vulnerable during migration. In the era before wildlife protection laws, the birds faced relentless pressure from market hunters who capitalized on their predictable flight paths and flocking behavior. They were often shot by the thousands in coastal marshes and inland prairies, their meat sold widely in American cities. At the peak of their abundance, some observers compared their numbers to those of the Passenger Pigeon, indicating that this was once one of the most common shorebirds in North America. However, such abundance proved to be a fatal illusion. With no seasonal limits, no regulation of harvests, and widespread access to firearms, their populations declined precipitously within just a few decades.

A Mysterious Disappearance and Scattered Hope

By the early 20th century, Eskimo Curlews had become an increasingly rare sight. Their flocks no longer filled the skies, and confirmed observations grew scarce. The last specimen definitively identified was collected in Barbados in 1963. Since then, a few unverified sightings have emerged, particularly from remote areas in Texas, the Caribbean, and even South America. These reports have fueled sporadic searches by ornithologists and birdwatchers, but none have yielded conclusive evidence—such as clear photographs, recordings, or genetic material—confirming the species’ survival. Unlike some other lost birds, the Eskimo Curlew left behind no breeding population in captivity, further complicating hopes for recovery.

An Urgent Lesson in Migratory Conservation

The likely extinction of the Eskimo Curlew is more than a historical footnote; it is a stark reminder of the vulnerability of migratory species, which depend on the integrity of multiple ecosystems across continents. A breakdown in any segment of their migratory route—whether breeding grounds, stopover sites, or wintering areas—can disrupt population dynamics and threaten long-term survival. For Alabama, the bird’s disappearance underscores the need to protect remaining coastal habitats and inland wetlands that serve as vital refuges for other migratory species. The fate of the Eskimo Curlew stands as a compelling argument for international cooperation in bird conservation and a warning about the consequences of inaction.

Conclusion

The disappearance of these four bird species from Alabama’s skies is a stark reminder that even abundant wildlife is not immune to extinction. While their stories differ in ecological nuance and historical context, common threads emerge: overexploitation, habitat destruction, and a failure to act before declines became irreversible. These cases also reflect an era when ecological systems were poorly understood and rarely protected. Today, Alabama is home to more than 400 bird species, many of which face similar pressures—from habitat fragmentation to climate change. The lessons learned from the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon, Carolina Parakeet, Ivory-billed Woodpecker, and Eskimo Curlew remain deeply relevant. They underscore the urgency of conservation, the need for scientific monitoring, and the responsibility to safeguard the delicate balance of biodiversity. Remembering what has been lost is essential to protecting what still remains.