Pigeons, known scientifically as Columba livia, are one of the most widespread and adaptable bird species on Earth. Commonly seen in city parks, rural farms, and even coastal cliffs, pigeons have evolved a highly efficient and well-adapted reproductive cycle that has contributed to their global success. Understanding the life cycle of pigeons—from egg to adulthood—reveals not only the resilience of these birds but also the intricate biology behind their growth and development.

Overview of the Pigeon Life Cycle

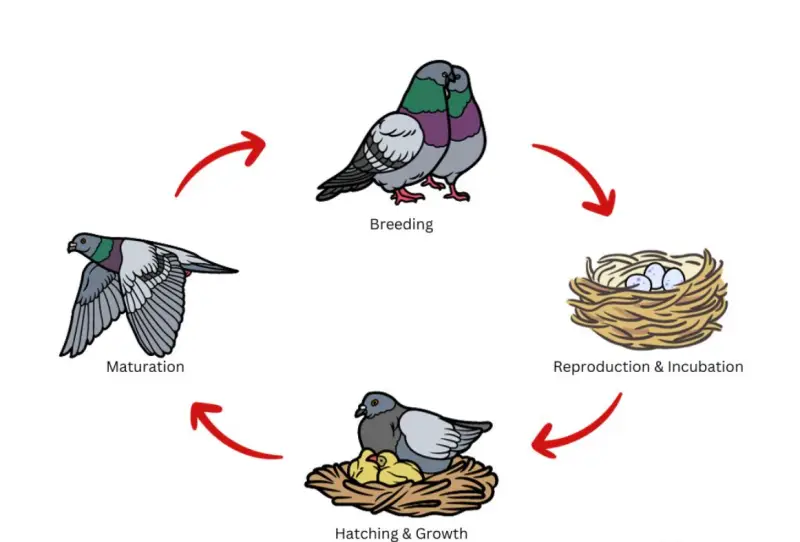

The life of a pigeon is a fascinating journey that unfolds in five interconnected stages, each one playing a vital role in shaping a fragile egg into a strong, self-sufficient flier. From the moment a parent selects a nesting site to the day their offspring takes its first flight into the open sky, the pigeon’s life cycle reveals a finely tuned process of growth, care, and transformation.

1. Egg Laying

It all begins with a pair bond. Once mated, a female pigeon lays a small clutch—typically just two smooth, white eggs—into a simple nest of twigs and straw. These eggs mark the start of new life and are fiercely protected by both parents.

2. Incubation

For the next 17 to 19 days, the eggs are kept warm and safe. Male and female pigeons share incubation duties, taking turns sitting on the eggs to maintain a stable temperature essential for embryo development. Inside the eggs, life stirs quietly as tiny organs, feathers, and beaks begin to take shape.

3. Hatching

With a series of weak pecks, the chick begins to crack open its shell using a temporary “egg tooth.” After hours of effort, it emerges into the world—naked, blind, and completely dependent on its parents for warmth, protection, and food.

4. Nestling Period (Squab Stage)

This is the stage of explosive growth. Fed with a rich substance called pigeon milk, the chick—known as a squab—grows rapidly in size and strength. Within weeks, it develops feathers, opens its eyes, and becomes more alert, still relying entirely on its parents for nourishment and safety.

5. Fledging and Adulthood

Around day 28 to 35, the young pigeon takes its first flight, entering the world as a fledgling. It begins exploring its surroundings and learning to forage. Within just a few months, it reaches full maturity, ready to form its own pair bond and repeat the cycle anew.

Together, these five stages form a fluid and efficient life strategy—one that enables pigeons to thrive in environments as varied as urban rooftops and remote cliffsides. Each phase builds on the success of the last, ensuring the survival of one of the world’s most adaptable and prolific bird species.

Egg Laying: The Start of New Life

The pigeon life cycle begins not with a sudden event, but with a quiet ritual of bonding and trust. Long before the first egg is laid, two adult pigeons engage in a courtship dance as old as the species itself—a graceful, almost ceremonial display of communication, connection, and cooperation.

Mating and Pair Bonding

Pigeons are monogamous by nature, and many pairs form lifelong bonds that persist across multiple breeding seasons. The male initiates courtship with a combination of behaviors: he struts in tight circles around the female, bobbing his head, puffing out his chest, and emitting soft, rhythmic coos. This is often followed by an elegant bowing display, where he lowers his chest, fans his tail slightly, and tilts his head upward in a show of intent.

If the female is receptive, the pair engages in mutual preening, gently nibbling at each other’s neck feathers. This bonding ritual not only solidifies their relationship but also reinforces trust—a crucial element in successful co-parenting.

Once bonded, the pair seeks out a nesting site that offers shelter, stability, and elevation. In the wild, this might be a rock ledge or tree branch. In urban environments, pigeons adapt by nesting on windowsills, building ledges, balconies, or even air conditioning units—anywhere that mimics a secure natural perch.

Nesting and Egg Production

The nest itself is modest, built from twigs, straw, and sometimes bits of debris scavenged from the surroundings. Though simple in design, it serves as the heart of the reproductive cycle.

After mating, the female lays two eggs per clutch, typically spaced a day apart. These eggs are smooth, oval, and pure white with a slightly glossy finish. Unlike species that lay large clutches to offset high chick mortality, pigeons take a different approach: they invest deeply in just two offspring, ensuring that both receive intensive care, warmth, and nutrition.

This strategy reflects the pigeon’s remarkable adaptability—by raising fewer young but providing them with high parental attention and nutrient-rich food, they increase the odds that each chick will survive, fledge, and thrive in the complex world beyond the nest.

Thus begins the quiet miracle of life: two small eggs nestled in a simple structure, guarded and warmed by a bonded pair, filled with the potential of the next generation.

Incubation: The Critical Warming Period

With two gleaming white eggs nestled safely in the nest, the next chapter of the pigeon’s life cycle begins: incubation, a phase where patience, warmth, and biological precision converge to turn stillness into life.

A Shared Responsibility

Once the second egg is laid, the parents begin full-time incubation. This task is shared between both male and female in a highly coordinated routine that underscores the strength of their bond. The male typically incubates during the day, giving the female time to feed and rest, while the female takes over through the night, maintaining uninterrupted warmth in the cooler hours. This continuous cycle ensures that the eggs are never left exposed to chilling temperatures or the watchful eyes of predators.

The Role of the Brood Patch

At the core of effective incubation lies a specialized structure called the brood patch—a featherless area on the belly of both parent birds. During breeding season, this patch becomes engorged with blood vessels, turning it into a highly efficient heat conductor. When the parent settles over the eggs, the warm skin of the brood patch directly transfers body heat to the eggs, keeping the internal temperature remarkably stable, even in fluctuating weather conditions.

This precise thermal control is critical. For 17 to 19 days, the embryos undergo rapid development. Inside the shell, tiny hearts begin to beat, wings and beaks form, and feather follicles emerge. Any major disruption in temperature or prolonged exposure to cold could stop this delicate process altogether.

Silent Vigil, Hidden Transformation

Throughout the incubation period, the parents remain alert but still. Unlike some species that turn eggs frequently or leave them unattended for long stretches, pigeons exhibit a quiet, almost meditative vigilance. They occasionally shift their position to rotate the eggs, ensuring even warmth and proper embryonic orientation, but otherwise sit in stoic focus, guarding their investment in the next generation.

This phase is largely invisible to outside observers, but within each egg, a dramatic transformation unfolds. From a cluster of dividing cells emerges a living creature—one uniquely equipped to enter the world weak, but ready to grow.

When the time is right, the next stage begins—not with a burst, but with a series of soft, rhythmic pecks from within. The chicks are preparing to hatch, and the quiet warmth of incubation will soon give way to the sounds of new life.

Hatching: Breaking Into the World

After more than two weeks nestled in quiet darkness, transformation reaches its final moment: hatching—a process both delicate and determined, marking the fragile beginning of independent life.

A Slow, Laborious Entrance

Inside the egg, the fully developed chick stirs for the first time with purpose. Armed with a temporary structure called an egg tooth—a small, sharp projection at the tip of its beak—the chick begins to peck at the inner shell wall in a slow, rhythmic pattern. This process, called “pipping,” can take anywhere from several hours to nearly a full day, depending on the chick’s strength and shell thickness.

The initial crack is small and barely visible, but it marks the start of a one-way journey. As the chick rotates inside the egg, it chips away in a circular path around the shell’s interior, creating a break line known as a “hatch ring.” Finally, with one last push, the top of the shell lifts free, and the newborn squab emerges—weak, wet, and blinking into the world for the first time.

Helpless, Yet Perfectly Designed

Pigeon chicks, often called squabs, hatch in a state known as altricial—completely helpless and undeveloped compared to precocial birds like ducks or chickens. They are blind, featherless, and barely able to lift their heads, relying entirely on the warmth and care of their parents.

But while they may appear vulnerable, they are perfectly adapted for the environment they’ve entered. Their underdeveloped state allows for rapid post-hatch growth, fueled by a unique parental adaptation that begins almost immediately.

Pigeon Milk: Nature’s Superfood

Within hours of hatching, the parents begin to feed their chicks a highly specialized substance called pigeon milk. Secreted from the lining of the crop—a muscular pouch in the throat used for food storage—this nutrient-dense fluid is rich in proteins, fats, and immune-boosting compounds.

Unlike seed mash or insect gruel fed by many birds, pigeon milk has a cheese-like consistency and is produced by both males and females. They regurgitate it directly into the chick’s mouth, nourishing the squab with everything it needs to grow quickly, develop feathers, and strengthen its immune system.

This unique feeding strategy allows pigeons to raise their young with remarkable efficiency, even in nutrient-scarce or urban environments. The result is a chick that, though born helpless, is soon growing at a pace that outstrips many other birds of similar size.

From this moment on, the pace of development accelerates dramatically—and the once-fragile chick will soon become a sleek, strong fledgling preparing for its first flight.

Nestling Stage: Rapid Growth in the Nest

Once hatched, pigeon chicks enter a period of intensive growth and transformation. Known as the nestling stage or squab phase, this is when the foundations for flight, independence, and survival are laid—quietly and swiftly within the protective shelter of the nest.

Pigeon Milk: A Unique Avian Adaptation

In the first week of life, nourishment comes in the form of a remarkable biological innovation: pigeon milk. Though it bears no resemblance to mammalian milk, this creamy, protein-rich secretion is equally essential. Produced in the crop lining of both male and female pigeons, it is regurgitated directly into the beak of the chick.

This semi-solid substance is loaded with:

-

Proteins and fats, for rapid cellular growth

-

Immune factors and antioxidants, to help build disease resistance

-

Water content, which helps hydrate chicks that cannot yet drink on their own

For the first 7 to 10 days, pigeon milk is the squab’s sole food source, enabling it to double in size within just a few days. Few other birds grow as quickly in their early days.

Feather Development and Growth

Around day 10, major physical changes begin. The squab’s eyes open, and pinfeathers—tiny tubes that will become full feathers—begin to emerge through the skin. This is the start of plumage development, transforming the pink, wrinkled chick into a more birdlike juvenile.

By week two, the chick’s skeletal structure strengthens, muscles thicken, and coordination improves. At this point, parents begin transitioning the squab’s diet from pure pigeon milk to softened seeds and grains, pre-digested and regurgitated into the chick’s mouth. This gradual shift prepares the young pigeon’s digestive system for adult food.

Dependency on Parental Care

Despite their rapid physical growth, squabs remain entirely dependent on their parents for warmth, protection, and nourishment during this period. They do not venture from the nest, and their underdeveloped feathers offer little insulation. The parents, in turn, continue to brood them through cold nights and feed them multiple times a day.

This intense care typically lasts 3 to 4 weeks, during which the squab’s size, behavior, and appearance begin to resemble that of an adult. By the end of this stage, the chick is usually fully feathered, alert, and strong enough to stand, flap its wings, and prepare for its first short flights.

The nestling stage is the heart of a pigeon’s early life—a time when quiet, invisible work gives rise to the visible marvel of flight-ready form. What begins as a helpless hatchling will soon step to the edge of the nest, eyes bright, wings poised, and instinct calling it forward into the sky.

Fledging: The First Flight

After nearly a month of intense growth, transformation, and parental care, the young pigeon reaches one of the most pivotal moments in its life: fledging—the moment it spreads its wings and leaves the nest for the very first time.

Physical Readiness for Flight

By 28 to 35 days old, the squab has undergone a remarkable change. It is now fully feathered, with strong wing muscles and well-developed flight feathers. The once-feeble chick that couldn’t lift its head is now a sleek juvenile capable of flapping, perching, and exploring its surroundings.

The parents instinctively reduce feeding frequency during this stage, encouraging the young bird to begin seeking independence. Hunger becomes a powerful motivator for movement—prompting the fledgling to test its balance, spread its wings, and eventually launch into its first fluttering flight.

Though awkward at first, this initial flight is a critical milestone. It may only carry the fledgling a few meters to a nearby ledge or rooftop, but it marks the transition from dependency to freedom.

Staying Close, Learning Fast

Even after fledging, young pigeons do not immediately sever ties with their parents. For several days—sometimes up to a week—they remain within close range of the nesting site, often still following their parents and begging for food. During this transitional period, they receive one final round of education:

-

How to forage effectively, learning what is edible and where to find it

-

How to recognize water sources and drink independently

-

How to navigate their environment, avoiding dangers and adapting to local rhythms

Parents may still provide occasional food, but fledglings gradually become more self-reliant, refining their flying technique with short practice flights and learning to land safely.

Building Confidence for Independence

This period of training and transition is essential. Fledglings must develop coordination, stamina, and environmental awareness to survive in the wild or urban world. As they grow more confident, they venture farther from the nest, integrating into local pigeon flocks and exploring new food sources.

Within just a few short weeks of fledging, most young pigeons are indistinguishable from adults, both in size and behavior. And in as little as five to seven months, they may form their own pair bonds, build their own nests, and begin the cycle anew—completing one of nature’s most efficient reproductive strategies.

Adulthood and Reproduction

With their first uncertain flights behind them and survival skills firmly in place, young pigeons step into the next chapter of their lives: adulthood. But in the world of pigeons, maturity arrives quickly—bringing with it the instinct to breed, bond, and begin the life cycle all over again.

Maturity: Early Developers with Fast Cycles

Pigeons are among the earliest-maturing birds of their size. Incredibly, most reach sexual maturity between 5 to 7 months of age. As soon as they’re capable of reproducing, they begin the search for a mate, often returning to familiar nesting territories to establish a new pair bond.

Once bonded, pigeons waste little time. Their rapid reproductive rhythm—a result of short incubation periods, fast chick development, and low clutch size—means a single pair can raise multiple broods in a single year. In warm, food-rich urban areas, it’s not uncommon for pigeons to nest year-round, producing six or more broods annually.

This high output, paired with attentive parenting and adaptable nesting habits, explains why pigeon populations thrive in nearly every environment humans inhabit.

Urban vs. Wild Lifespan: The Role of Environment

A pigeon’s lifespan is shaped as much by its environment as by its biology. In the wild, feral pigeons face numerous threats: predators like hawks, falcons, and cats; extreme weather; and competition for food. As a result, their average lifespan hovers around 3 to 6 years.

In contrast, pigeons raised in captivity—or living in protected, low-risk environments—can live well over a decade. With access to consistent food, shelter, and veterinary care, domestic pigeons have been known to reach ages of 15 years or more, and some have even lived into their 20s.

Regardless of where they live, however, pigeons are remarkably resilient. Their combination of early maturity, frequent breeding, and flexible survival strategies makes them one of the most successful avian species on the planet.

From fledgling to full-grown breeder in just a matter of months, the adult pigeon carries forward not only its own genes, but also a legacy of adaptation and survival perfected over thousands of years.

Multiple Broods and Continuous Nesting

Among all the traits that make pigeons such prolific survivors, few are more impressive than their ability to nest almost continuously throughout the year. This capacity for rapid and repeated breeding is not just an evolutionary advantage—it’s the engine that fuels their vast populations in cities around the world.

A Species That Never Stops Nesting

Unlike many birds that breed only in spring or early summer, pigeons are not bound by seasonal cycles. In fact, under the right conditions—particularly in urban environments—they can breed year-round. With abundant food sources like scattered grains, trash scraps, or handouts from humans, and with ample nesting spots tucked into rooftops, balconies, and building crevices, pigeons face few natural barriers to reproduction in the city.

In these conditions, a single pair of pigeons may raise five, six, or even more broods per year. This high reproductive output far exceeds that of many wild bird species and is one of the key reasons pigeons thrive in dense, human-populated areas.

Overlapping Nest Cycles: Efficiency at Its Peak

Even more remarkable is the pigeon’s ability to overlap breeding cycles. Within days of their fledglings leaving the nest, the female is often ready to lay a new clutch of eggs, sometimes in the very same nest. Meanwhile, the male may continue caring for the recently fledged young—guiding them to food sources—while the female begins incubating the next generation.

This relay-like system of continuous nesting creates an almost unbroken chain of reproduction, ensuring that there are always chicks in the nest, fledglings in the air, and new eggs on the way.

The Impact on Population Growth

This relentless pace of reproduction allows pigeons to bounce back rapidly from population declines due to predation, disease, or environmental changes. It also makes population control efforts in cities notoriously difficult, as even a small surviving group can quickly repopulate an area if conditions remain favorable.

More than just a curiosity, this biological strategy of continuous breeding is a masterclass in evolutionary success—balancing high parental care with high reproductive frequency to ensure long-term survival in a world full of change.

Conclusion: A Life Built for Resilience

From fragile eggs to confident fliers navigating city skies, pigeons live fast, reproduce often, and adapt easily. Their life cycle reflects a perfect balance between parental investment and reproductive output, allowing them to flourish in environments from coastal cliffs to concrete jungles.

Understanding the pigeon’s life cycle offers more than just curiosity—it reveals why this species has become one of the most successful and familiar birds in the world.