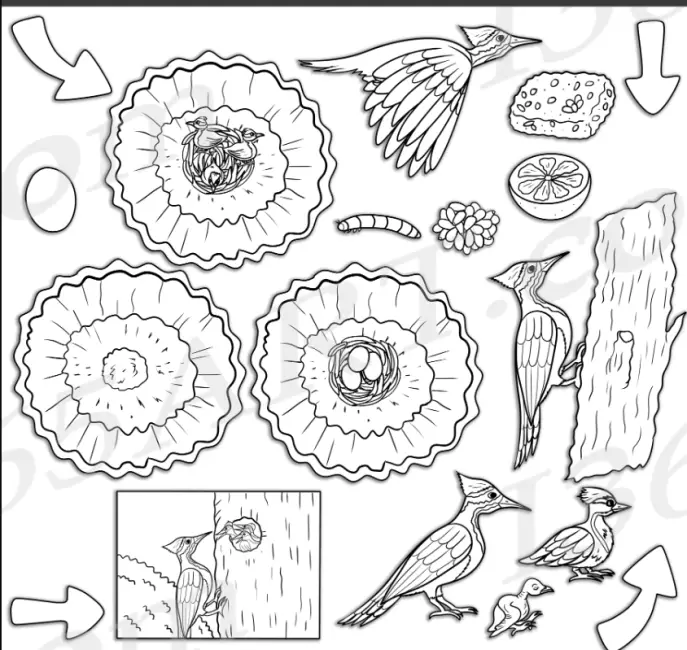

Woodpeckers are among the most fascinating birds in the avian world, known for their rhythmic pecking, strong bills, and specialized anatomy. But before they begin drumming on tree trunks, every woodpecker starts life as a tiny, helpless egg inside a dark nest cavity. In this article, we explore the complete life cycle of a woodpecker—from the moment of egg-laying to the day it carves its own mark on the forest.

Breeding and Nesting Season

Courtship and Mate Selection

The woodpecker breeding season usually begins in spring, when rising temperatures and longer days trigger hormonal changes. Males begin performing courtship displays that include drumming, wing spreading, and vocal calls. Drumming, in particular, serves both to attract a mate and to declare territory.

Once a pair forms, they often stay together for at least a season—some species are monogamous for life. Both birds participate in selecting a nesting site, which is almost always an excavated cavity in a dead or decaying tree, chosen for its soft wood and protection from predators.

Nest Excavation and Egg Laying

The nest cavity is created by both sexes, though males typically do more of the digging. This process can take days or even weeks. Once the hollow is deep enough and the chamber is ready, the female lays a clutch of 3 to 7 eggs, depending on the species.

Woodpecker eggs are small, white, and unmarked—perfectly camouflaged in the dark interior of the tree cavity. Because the nest is hidden from light and lined only with wood chips, the parents take great care to incubate and protect the eggs.

Incubation and Hatching

Shared Incubation Duties

Once the clutch of eggs is laid deep within the excavated nest cavity, a meticulously coordinated incubation period begins. Lasting between 11 and 14 days—depending on species, ambient temperature, and geographic location—this stage is marked by intense parental cooperation. In many species of woodpeckers, such as the Downy Woodpecker (Dryobates pubescens), both the male and female share incubation duties almost equally, though the division of labor may vary slightly by species.

Typically, the female incubates during daylight hours, while the male assumes responsibility overnight, allowing each bird time to forage and maintain its own energy reserves. This alternating rhythm ensures that the developing embryos are kept at a stable temperature, generally between 36°C and 38°C, critical for proper cell division and organogenesis. The cavity’s insulated environment helps buffer against external temperature fluctuations, but it is the constant brooding and vigilant repositioning of the eggs that ensure their uniform development.

During this phase, both parents begin to exhibit heightened territorial aggression, frequently defending the nest from rival woodpeckers, snakes, squirrels, and even larger birds of prey. Intruders are met with alarm calls, drumming, and in some cases, physical confrontation. The interior of the cavity remains unlined, save for wood chips produced during excavation, which provide slight cushioning and absorb moisture.

Hatching and Early Nest Life

After nearly two weeks of incubation, the eggs begin to hatch, often within a 24-hour window. The chicks emerge using a specialized structure on their upper bill called the egg tooth, which helps them break through the brittle eggshell. At hatching, woodpecker chicks are altricial—born blind, naked, and completely helpless. Their eyes remain closed for the first 7 to 10 days, and their skin is translucent, exposing a faint vascular network beneath.

Because they lack down feathers or the ability to thermoregulate, the hatchlings must be constantly brooded by one parent while the other forages. In the early post-hatching period, adults alternate rapidly between nest defense, incubation of remaining unhatched eggs (if any), and feeding. The rate of feeding is intense—up to 20 visits per hour, depending on food availability and chick age.

The diet of newly hatched chicks consists almost entirely of soft-bodied insects, insect larvae, and small arthropods, regurgitated or gently inserted directly into the chick’s gaping mouths. The meal composition is extremely protein-rich, fueling rapid tissue and skeletal development. As days progress, the chicks begin to vocalize faintly and respond to vibrations from the adult’s approach, signaling the first signs of neurological and sensory maturation.

By the end of the first week, the chicks’ skin darkens, and pinfeathers begin to erupt from the feather tracts. Though the cavity remains dark, their growing sensitivity to light and touch helps orient them toward feeding parents. Despite being confined in a tight space, they begin jostling for feeding position—an early sign of competitive behavior that continues throughout their development.

This stage, while sheltered and protected, is one of extreme vulnerability. The survival of the brood depends on parental vigilance, a reliable food supply, and stable environmental conditions within the nest cavity. It is the quiet, unseen foundation of every future drumming display—an intimate, high-stakes phase where each heartbeat and feeding visit shapes the forest drummers of tomorrow.

Growth and Development

Feather Development and Sensory Awareness

In the first week after hatching, woodpecker chicks enter a period of rapid morphological and neurological transformation. By day 5 to 7, their once-translucent skin begins showing signs of pinfeather emergence—small tubular sheaths that mark the initial formation of contour feathers. These structures erupt from pre-determined tracts across the head, wings, and back, eventually unfurling into the stiff plumage necessary for thermoregulation and flight.

During this same window, the chicks’ eyelids begin to separate, gradually revealing dark, glossy eyes. Visual perception improves rapidly, followed closely by auditory awareness. By day 10, the chicks respond to the vibrations of approaching parents and ambient light filtering through the nest entrance. Their movements become more deliberate, and they begin to lift their heads, rotate toward sounds, and jostle more actively for position during feeding.

Neuromuscular development also accelerates. The once-flaccid neck and limb muscles begin supporting basic postural control. Simultaneously, the keratinized tissue in the bill begins to harden and elongate, setting the foundation for one of the woodpecker’s most iconic tools: a strong, chisel-shaped beak capable of boring into bark in search of insects.

Throughout this stage, parental care remains intense. Adults feed the chicks at intervals of 10 to 20 minutes, depending on resource availability. Equally critical is the removal of fecal sacs, mucus-coated waste packages excreted by the chicks. This behavior ensures that the nest cavity remains sanitary, minimizing the risk of bacterial or fungal infection in the damp, enclosed environment.

Fledging and First Flight

Between 18 and 30 days post-hatching, depending on species, nutrition, and ambient conditions, the chicks enter the fledging phase. This is marked by a notable behavioral shift: the young woodpeckers begin climbing toward the entrance of the cavity, using their growing claws to grasp the interior wall while fluttering their now fully feathered wings. They peer cautiously into the outside world, often vocalizing and responding to their parents’ calls.

The first flight—technically a controlled glide rather than powered flight—usually takes place when wing musculature and coordination reach a critical threshold. The fledgling launches from the cavity and descends to a nearby tree or low perch, often under parental supervision. Initial flights are clumsy and short, but coordination improves quickly over the following days.

Though they have left the nest, these juvenile woodpeckers are not yet self-sufficient. For up to two or three weeks, they remain under parental care, frequently following adults through the forest, begging with high-pitched calls, and watching attentively as their parents probe bark or glean insects. This post-fledging period is essential for learning complex survival behaviors such as:

-

Foraging techniques, including how to extract grubs from under bark or sip sap from tree wounds

-

Predator awareness, such as freezing in response to overhead shadows or alarm calls

-

Territorial navigation, learning which trees are safest for shelter or feeding

By the end of this phase, the juvenile’s feathers are fully developed, its bill hardened, and its coordination nearly adult-like. Though it may still share some subtle plumage differences—such as duller coloration or an incomplete crown patch—it is now ready to begin life as an independent driller, carving its own place in the forest soundscape.

Juvenile Stage and Learning to Drum

Mastering Foraging and Climbing

Once fledglings reach independence, they enter the juvenile stage—a critical period of refinement where instinctual behaviors are honed into functional survival strategies. While still under occasional parental observation, juvenile woodpeckers begin to explore their environment more extensively, venturing farther from the natal site and experimenting with the behaviors that will define their adult lives.

Among the most important skills developed during this stage is foraging proficiency. Juveniles begin probing bark crevices, inspecting twigs, and pecking at soft wood surfaces in search of insects. Their diet becomes more varied, incorporating ants, beetle larvae, caterpillars, spiders, and, depending on species, tree sap, berries, acorns, and even nuts. While their technique is initially imprecise, repetition and observation improve their success rates dramatically.

Equally essential is the continued improvement of vertical climbing mechanics. This behavior is made possible by a suite of physical adaptations unique to woodpeckers. Most notable is the zygodactyl foot structure, with two toes pointing forward and two backward—offering superior grip on vertical surfaces. These feet, in tandem with stiff, acuminate tail feathers, allow the bird to use its tail as a third limb, bracing itself as it ascends tree trunks. Juveniles practice this tripod-like posture obsessively, developing the balance and coordination required for life in the vertical strata of the forest.

The First Drums

Perhaps the most iconic behavioral milestone of the juvenile stage is the onset of drumming behavior—a rhythmic pecking on resonant surfaces that functions not for excavation but for communication. Unlike most songbirds that vocalize using syrinx-generated melodies, woodpeckers communicate territorially and socially through percussion.

The first attempts at drumming are often clumsy and sporadic. Juveniles may strike at bark, branches, or hollow stumps with irregular spacing and uneven force. These “practice drums” likely serve a dual function: helping the bird learn acoustic mechanics and allowing it to test the resonance of various substrates. Over time, as the juvenile strengthens its neck muscles and sharpens its rhythm, the drumming becomes more structured—characterized by rapid, even beats unique to its species.

This acoustic signature plays a vital role in adulthood. It acts as a non-vocal song, advertising territory to rivals, attracting potential mates, and reinforcing species identity. In many species, drumming sequences are so consistent that they can be used by researchers to distinguish between individuals or populations.

By the close of the juvenile period—typically at 2 to 3 months of age, though species-dependent—the young woodpecker is a proficient climber, a capable forager, and an articulate drummer. Plumage has now fully matured, and behavioral patterns mimic those of adults. Equipped with physical tools and learned behaviors, the bird is ready to establish its own territory, excavate a new nest cavity, and begin the breeding cycle anew.

Adulthood and Reproduction

Establishing Territory

By the time the next breeding season arrives—typically in early spring—most woodpeckers reach sexual maturity, often by 12 months of age. At this point, juveniles disperse from their natal area and seek out unclaimed or weakly defended territories, a behavior that reduces inbreeding and promotes genetic diversity within populations.

Establishing a territory involves more than simply finding a suitable tree. Adult woodpeckers must secure feeding grounds, locate potential nesting sites, and actively defend boundaries through both physical displays and acoustic signaling. Drumming becomes more intense, regular, and species-specific, with individuals producing distinct rhythmic patterns to assert dominance and attract mates. The volume, frequency, and duration of drumming often correlate with individual fitness, functioning similarly to the complex songs of passerines.

When it comes to nesting, adults may reuse previously excavated cavities, especially if they remain structurally sound. In some species, individuals will return to the same nesting tree year after year, expanding or reshaping the cavity as needed. However, many woodpeckers—particularly in the Picinae subfamily—are prolific excavators, often creating new nest sites annually. These abandoned cavities become valuable habitat for secondary cavity nesters such as owls, chickadees, and squirrels, making woodpeckers ecosystem engineers within forest communities.

Territorial aggression peaks during the breeding season. Woodpeckers may engage in bill fencing, aerial chases, and vocal confrontations to repel intruders. This defensive behavior ensures access to high-quality nesting and foraging resources—critical factors for reproductive success.

Lifespan and Survival

Despite their robust adaptations and specialized niche, woodpeckers face numerous natural and anthropogenic threats. Predators such as snakes, raptors, and tree-climbing mammals (e.g., raccoons, squirrels, and martens) target both eggs and chicks. Adults are vulnerable during cavity excavation and foraging, especially in open habitats or fragmented forests.

Habitat loss remains the most pressing challenge. The removal of dead or dying trees—essential for nesting and drumming—directly reduces breeding opportunities. Urbanization, deforestation, and monoculture forestry practices fragment suitable territories and isolate populations.

Yet woodpeckers are remarkably resilient when conditions are favorable. Lifespan varies significantly by species, with smaller species like the Downy Woodpecker (Dryobates pubescens) typically living 4 to 6 years, while larger species such as the Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) may survive for over 10 years in the wild. Individuals residing in protected habitats with abundant deadwood and minimal human disturbance tend to enjoy longer lifespans and higher reproductive success.

Long-term studies have shown that woodpeckers exhibit site fidelity, returning to the same territory across multiple seasons. In stable environments, these birds contribute to the continuity of forest ecosystems by controlling insect populations and facilitating nesting opportunities for other species.

As adults, woodpeckers not only reproduce but also serve as keystone organisms, shaping the ecological fabric of their woodland homes—one peck at a time.

Conclusion

From a tiny, unfeathered hatchling to a forest-dwelling drummer echoing through the trees, the life of a woodpecker is one of transformation, adaptation, and survival. Each stage—from the warmth of the nest to the powerful rhythm of adult drumming—reflects a bird finely tuned to life in vertical worlds.

Understanding the life cycle of woodpeckers not only reveals the hidden intricacies of their biology but also emphasizes the importance of conserving their habitats. These master carvers are more than just woodland soundtracks—they are essential members of forest ecosystems, contributing to insect control, tree health, and cavity creation for other wildlife.