Sparrows are among the most familiar and widespread birds in the world, often seen flitting through cities, farmlands, and forests. Behind their tiny frames lies a fast-paced and fascinating life cycle that spans from delicate eggs to agile adult fliers. Understanding this cycle offers insight into their survival strategies, ecological importance, and the challenges they face from nest to sky.

Nest Building and Egg Laying

Choosing the Perfect Nesting Site

Sparrows are highly adaptable birds and exhibit remarkable resourcefulness when it comes to choosing nesting sites. Their preference is driven by two critical needs: shelter and food availability. In the wild, they may select dense shrubs, tree hollows, or tangled vines. In urban and suburban areas, however, they take full advantage of human structures—nesting in gutters, roof eaves, ventilation ducts, crevices in walls, and even unused light fixtures or flowerpots.

House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), in particular, are known for their bold colonization of artificial environments. They can coexist closely with humans, often nesting just feet away from doors or windows. Safety from predators, proximity to insect-rich gardens or bird feeders, and access to dry building materials all influence nest site selection.

The Architecture of a Sparrow Nest

Nest construction is a collaborative effort, but it usually begins with the male collecting coarse materials like twigs, straw, and dried grass. These form the outer structure, which acts as a barrier against the elements. Once a basic framework is established, the female takes charge of the interior design. She meticulously lines the cup-shaped nest with softer elements such as feathers, rootlets, animal hair, or bits of paper and cloth, creating a warm, cushioned environment ideal for incubation.

This two-layered architecture serves critical functions. The outer shell offers camouflage and structure, while the inner lining ensures temperature stability and comfort for developing embryos. In some cases, sparrows may reuse old nests or refurbish abandoned ones from previous seasons.

Egg Formation and Incubation Behavior

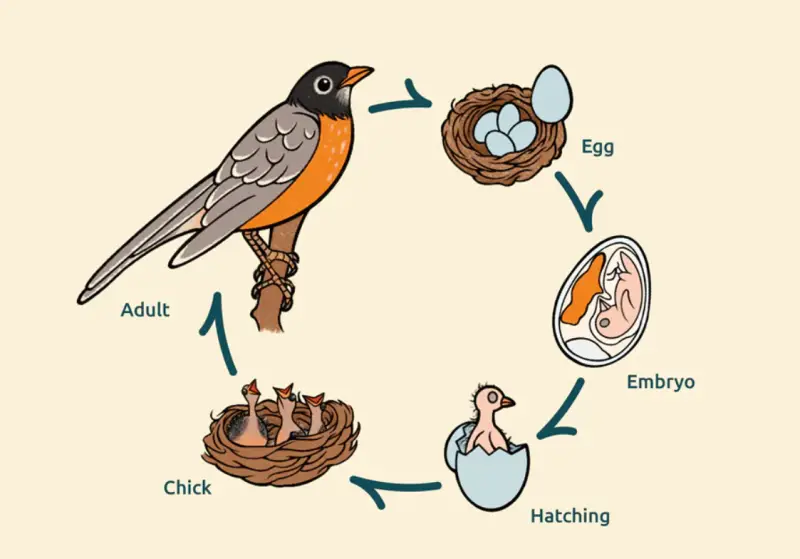

After the nest is complete, the female lays a clutch of 3 to 7 eggs over several days, typically one egg per day. The eggs vary in appearance, ranging from off-white and bluish-gray to speckled or streaked, depending on the species and individual genetics. Each egg measures about 2 centimeters in length—roughly the size of a jellybean—but carries the vital genetic and nutritional blueprint for a future sparrow.

Once the final egg is laid, full-time incubation begins. The female sits tightly on the nest, her warm brood patch (a featherless area on the abdomen) directly transferring heat to the eggs. Incubation lasts between 10 and 14 days. During this period, the developing embryos require a constant temperature—typically around 37.5°C (99.5°F). Even brief exposure to cold can interrupt or impair embryonic growth.

Although the female handles most incubation duties, the male often plays a supporting role. He may guard the nest site from rival sparrows or predators such as snakes, cats, and crows. He also provides food for the female during long incubation periods, allowing her to remain on the eggs for extended stretches.

The sparrows’ diligence during this phase sets the foundation for successful hatching. Their ability to construct well-insulated nests and maintain optimal warmth is essential for embryonic development and ensures the next generation begins life under the best possible conditions.

Hatching and Early Nestling Stage

Altricial Beginnings: Fragile Yet Rapidly Developing

After approximately 10 to 14 days of incubation, the sparrow eggs hatch almost simultaneously. What emerges are altricial hatchlings—young birds born in a highly undeveloped state. They are blind, naked, and unable to regulate their own body temperature. Their survival during this vulnerable phase depends entirely on the vigilance and dedication of their parents.

Despite their fragility, these newborns are biologically primed for rapid development. Their skin appears pink and translucent, and their heads seem disproportionately large due to underdeveloped skeletal muscles. One of their most remarkable features at this stage is the bright yellow or reddish coloration inside their open beaks. This visual cue, known as a gape flange, stimulates adult sparrows to feed them accurately and consistently—an evolutionary adaptation that enhances chick survival.

Feeding: A Demanding Parental Task

The first few days of a chick’s life are a race against time to build strength, regulate internal body functions, and initiate feather development. To meet these intense metabolic demands, parents feed their chicks an almost constant supply of soft-bodied invertebrates—primarily caterpillars, aphids, small beetles, and insect larvae. These protein-rich meals supply essential amino acids and lipids that drive the rapid formation of muscles, organs, and nervous tissue.

During peak feeding periods, adult sparrows may make over 200 trips to and from the nest per day. They often alternate shifts to ensure that each chick receives adequate nourishment.

Developmental Milestones in the First Week

Physical changes occur swiftly. Around day 3 to 5, sparse rows of pinfeathers—encased in keratin sheaths—begin to emerge across the head, back, and wings. These early feathers not only provide the beginnings of insulation but also mark a critical transition toward fledging readiness.

By day 6 to 8, the nestlings’ eyes begin to open, and they start reacting to light, sound, and movement. Their coordination improves, and they begin jostling for position in the nest, especially when they sense a parent returning with food.

Hygiene and Nest Maintenance

Cleanliness is vital in the cramped space of a sparrow nest. Both parents engage in waste management, removing fecal sacs—gelatinous sacs that contain the chicks’ droppings. These sacs are carried away from the nest or occasionally consumed by the parents, preventing the buildup of odor or waste that might attract predators or pathogens.

This combination of attentive care, efficient feeding, and meticulous hygiene gives the chicks the best chance of surviving into the fledgling stage. By the end of the first week, sparrow nestlings are well on their way to becoming active, feathered juveniles.

Fledging: Learning to Fly

Preparing for First Flight

By day 12 to 17 post-hatching, the nestlings approach a critical milestone: fledging. At this point, their plumage has developed sufficiently—particularly the primary and secondary flight feathers on the wings and tail—to support short bursts of flight. Down feathers are replaced by juvenile contour feathers that provide insulation, aerodynamics, and the appearance of a miniature adult.

As their musculature strengthens, the chicks begin performing “winger-cising”—a series of vigorous wing stretches and flaps within the confined nest. These movements are both physical preparation and instinctual practice. The chicks also engage in visual exploration, poking their heads out of the nest to assess the surrounding environment. This behavior sharpens their spatial awareness and readiness to navigate unfamiliar terrain.

Parental behavior plays a pivotal role during this transition. Adult sparrows call to their young from nearby perches and may present food just outside the nest to lure them out. This behavior creates a motivational push for chicks to leap and glide—often resulting in clumsy, fluttering descents to the ground or nearby shrubs. The first flight is rarely elegant, but it is a monumental leap toward independence.

Post-Fledging Parental Support

Despite leaving the nest, fledgling sparrows are far from self-sufficient. For the next 7 to 14 days, they remain under the watchful care of their parents, often seen following adults with fluttering wings and open mouths—a behavior known as “post-fledging begging.”

During this time, parents continue to provide food but gradually reduce feedings to encourage self-foraging. The fledglings mimic parental behaviors, observing how to:

-

Identify nutritious seeds, grains, and insects

-

Recognize predator calls and visual threats

-

Choose suitable perches and sheltering spots

-

Navigate through dense vegetation and human-made structures

Learning these survival skills is critical. Mortality is highest during this stage, as fledglings are vulnerable to predators, poor weather, and human disturbances. However, those that adapt quickly and feed efficiently soon begin showing independence, signaling the end of their parental dependence.

By the third or fourth week after hatching, most fledglings are capable of sustained flight and fully foraging on their own, officially entering the juvenile stage.

Juvenile Development and Maturation

Molting and Beak Strengthening

Once fledglings achieve stable flight and foraging ability, they enter the juvenile phase, a period of rapid physiological and behavioral refinement. One of the most significant transformations during this stage is partial molting. Juveniles begin to shed their soft, downy feathers and replace them with more structured, melanin-rich contour feathers that offer improved insulation, water resistance, and camouflage. This molt marks their visual transition into adult-like birds, although subtle color differences often distinguish them for a few more weeks.

Simultaneously, the beak—initially soft and pale—undergoes keratinization, becoming harder, darker, and more efficient at cracking seeds and manipulating insects. This structural refinement is essential, as sparrows transition from a diet partially reliant on parental feeding to full dietary independence.

Young sparrows also develop neuromuscular coordination critical for precision pecking, aerial maneuvering, and threat response. Their vocalizations begin to shift as they listen to adult calls and songs, an important step for social bonding and future mate attraction.

Practicing Adult Behaviors

Juveniles instinctively begin rehearsing adult behaviors shortly after fledging. These include:

-

Ground foraging, where they shuffle through debris, leaf litter, or grass to uncover seeds and insects

-

Dust bathing, a behavior that removes parasites and maintains feather health

-

Sunbathing, which assists with vitamin D synthesis and feather drying

-

Territorial fluttering or wing-spread displays, especially in males preparing for the next breeding season

During this stage, they commonly form loose flocks with siblings or other nearby juveniles. These ephemeral social groups provide safety in numbers and increase foraging efficiency. Within these flocks, sparrows begin to learn complex social hierarchies, including pecking order, dominance, and cooperative alert systems.

Reaching Sexual Maturity

Most sparrows reach sexual maturity between 3 and 4 months of age, depending on species and environmental conditions. Their gonads mature, hormone levels rise, and, by late summer or early spring of the following year, they are ready to breed.

For early-season hatchlings, this development may be rapid enough to support a second breeding attempt within the same year, particularly in warmer climates with long breeding windows. Others disperse from their natal territories in search of mates and nesting grounds, thereby continuing the life cycle.

By this stage, juvenile sparrows have not only adopted the physical characteristics of adults but have also mastered the ecological and social skills essential for survival—flight, feeding, flocking, and courtship—thus fully entering adulthood.

Lifespan and Reproductive Potential

How Long Do Sparrows Live?

The average lifespan of a wild sparrow ranges from three to five years, though many individuals face steep odds in their first year. Predation, exposure to extreme weather, collisions with human structures, and disease contribute to high juvenile mortality. In fact, more than half of fledglings may perish before reaching adulthood.

However, in ideal conditions—with abundant food, safe nesting sites, and minimal human interference—some sparrows have been recorded living up to eight or even ten years. Captive sparrows, or those in controlled environments like wildlife sanctuaries, may live longer due to reduced threats.

Despite this relatively short life expectancy, sparrows compensate through remarkable reproductive productivity.

A Strategy of High Reproductive Output

Sparrows, particularly species like the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) or Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia), follow a “live fast, reproduce often” strategy. In temperate or subtropical climates, they may produce two to four broods per breeding season, with each clutch containing three to seven eggs. Under favorable circumstances, a single breeding pair can raise over a dozen fledglings per year.

This high reproductive rate helps maintain stable populations despite environmental pressures. It also allows sparrows to quickly recolonize areas after disturbances such as storms, habitat loss, or predator influx.

Such a reproductive strategy makes sparrows resilient ecological generalists, capable of thriving in a wide range of habitats—from rural grasslands to densely populated cities. Their rapid life cycle ensures that even if individuals perish young, the population continues to grow and adapt.

The Role of Environment in Sparrow Development

Natural and Urban Challenges

From hatching to adulthood, a sparrow’s development is deeply influenced by environmental conditions. In natural ecosystems, sparrows rely on a mosaic of resources: native grasses for seed foraging, trees or shrubs for nesting cover, and abundant insect populations during breeding season. However, these resources are increasingly under pressure due to habitat loss, agricultural intensification, and climate change.

In urban and suburban landscapes, sparrows—especially House Sparrows—have shown remarkable adaptability. They nest in roof crevices, feed on human food waste, and forage under bird feeders. While urban settings provide year-round shelter and access to food, they also present unique challenges. Pollution, noise, light disturbances, and nutrient-poor human scraps can negatively affect health, reproduction, and chick development. Urban environments also increase exposure to diseases and competition from invasive species like starlings.

Supporting Sparrows in Your Area

Conservation efforts—even at the backyard level—can play a critical role in sparrow survival. Here’s how to help sparrows thrive in both rural and urban settings:

-

Grow native plants and grasses: These provide natural seeds and attract insects for protein-rich diets during the breeding season.

-

Limit pesticide use: Chemicals reduce insect populations and may poison sparrows indirectly through contaminated prey.

-

Offer nesting opportunities: Nest boxes, brush piles, or preserved hedgerows give sparrows safe sites to raise their young.

-

Keep clean water available: Birdbaths or shallow dishes with fresh water help sparrows stay hydrated and clean, especially in hot or dry seasons.

-

Plant for all seasons: Year-round habitat diversity ensures access to food and shelter, even in winter months.

By fostering diverse, healthy environments, we support not just sparrows but the broader network of birds, pollinators, and native species that depend on shared ecosystems.

Conclusion

The life cycle of a sparrow is a story of speed, precision, and resilience. From the moment a fragile egg is laid to the instant a young bird takes its first leap into the air, every stage is finely tuned to survival. Understanding and appreciating these stages not only deepens our connection with nature but also reminds us of the delicate balances that sustain life in every corner of our world.