The little auk, also known as the dovekie, is one of the smallest seabirds in the Northern Hemisphere. Despite its diminutive size, this bird performs one of the most remarkable migrations in the world. Each year, millions of little auks leave the icy cliffs of the Arctic and travel immense distances across the North Atlantic. Their journey is demanding, unpredictable, and shaped by seasonal cycles that have remained constant for thousands of years.

Understanding why little auks migrate so far requires a deeper look at their ecology and behavior. These birds depend on specific marine conditions, rich feeding grounds, and stable nesting sites. Their migration reflects a delicate balance between food availability, climate patterns, and survival instincts. Everything from ocean temperature to Arctic daylight influences the timing and direction of their seasonal movements.

This article explores the science behind little auk migration. It reveals why these tiny seabirds undertake such long journeys, how they navigate vast oceans, what environmental forces shape their flight, and why this migration remains one of the great natural phenomena of the far North. By the end, you will understand how a bird weighing only a few ounces manages to complete one of the most dramatic migrations on Earth.

Understanding the Little Auk

Physical characteristics and adaptations

The little auk is a compact seabird with a short neck, rounded wings, and a dark, contrasting plumage that helps it blend into rocky cliffs and open water. It weighs around 150 grams on average and measures less than twenty centimeters in length. Despite its small size, the bird possesses a sturdy body designed for both flying long distances and diving to impressive depths.

Its wings are relatively short and narrow, which allows rapid wingbeats during flight. This wing structure is also ideal for underwater propulsion. Little auks use their wings to “fly” beneath the surface while pursuing small crustaceans. Their legs are placed far back on the body, promoting stability in water but making land movement limited and awkward. These adaptations demonstrate a strong evolutionary focus on life at sea.

The bird’s dense feathering provides insulation during frigid Arctic winters. A layer of waterproof feathers protects the skin from cold seawater, while air trapped in the plumage helps maintain buoyancy. These traits are essential for a species that spends most of its life in the harshest climate zones on Earth.

Habitat preferences and distribution

Little auks breed in colonies on steep, rocky slopes in the High Arctic. They nest among boulders and crevices where predators struggle to reach. These breeding grounds are located in Greenland, Svalbard, Franz Josef Land, Novaya Zemlya, and parts of Arctic Canada. The colonies grow extremely large, sometimes numbering millions of individuals in a single area.

During the nonbreeding season, little auks disperse across vast sections of the North Atlantic. They travel from deep Arctic waters to regions near Iceland, Norway, Newfoundland, and occasionally the North Sea. These movements depend on ocean currents and the distribution of plankton, the birds’ primary food source.

Little auks are closely tied to cold-water ecosystems. Their migration routes follow areas with nutrient-rich upwellings, where marine life flourishes. These locations offer reliable feeding opportunities throughout winter.

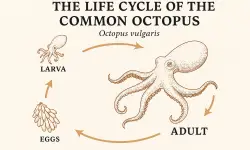

Life cycle and seasonal changes

The life cycle of the little auk is closely aligned with Arctic seasons. They arrive at breeding colonies in late spring when snow begins to melt. The period of midnight sun offers continuous daylight, allowing adults to forage throughout the day. This constant feeding helps supply energy for chick rearing.

After hatching, chicks grow rapidly. They fledge within a few weeks, leaving the colony and heading to sea. Adults follow soon after, beginning their long migration away from the Arctic. As autumn progresses, the birds move into wintering areas where they remain until the following spring.

These seasonal transitions shape the timing and rhythm of migration. The little auk’s survival hinges on its ability to move between regions that offer food, warmth, and safety throughout the year.

Why Little Auks Migrate

Seasonal food availability

The primary reason little auks migrate is to access food. During summer, the Arctic becomes one of the most productive marine environments on Earth. Sunlight triggers explosive growth of plankton and other microscopic organisms. These form the foundation of the food chain and support vast numbers of fish, crustaceans, and seabirds.

Little auks depend heavily on zooplankton, particularly copepods, which thrive in cold Arctic waters. These prey items are abundant near breeding colonies during summer, providing nourishment for both adults and their rapidly growing chicks.

When winter arrives, the Arctic marine ecosystem changes drastically. Ice forms across large regions, daylight declines, and productivity drops. Zooplankton sink to deeper waters, becoming harder for birds to reach. Migration allows little auks to exploit southern waters where food remains available.

Without moving south, little auks would face severe food shortages. Their migration therefore represents an essential survival strategy tied directly to the seasonal availability of prey.

Avoiding Arctic winter darkness

The Arctic winter brings extended periods of darkness. In some regions, the sun does not rise for months. These conditions make visual hunting extremely challenging. Because little auks rely on sight to locate prey underwater, remaining in the Arctic throughout winter would limit their ability to feed effectively.

Migrating south allows them to stay in regions with more daylight. Although winter days remain shorter than summer days, they still provide enough light for the birds to hunt. Even slight increases in daylight improve feeding efficiency and reduce energy loss.

This need for light has shaped migration routes over thousands of years. The birds follow paths that ensure consistent access to open water and workable light conditions through the darkest months.

Changes in sea ice and ocean conditions

Sea ice plays a major role in shaping little auk migration patterns. In late summer and autumn, sea ice begins to expand, covering coastlines and reducing access to open water. As ice spreads, little auks move southward toward areas with less coverage.

Ice-free waters offer more consistent feeding opportunities. The birds concentrate in regions where warm currents meet cold water, creating zones of high productivity. Such areas include the Labrador Sea, the Barents Sea, and waters surrounding Iceland and Jan Mayen Island.

This movement away from encroaching ice ensures survival through winter. When spring returns and ice retreats, the birds move north again to begin the breeding cycle.

How Little Auks Navigate Vast Distances

Ocean currents as natural pathways

Little auks use major ocean currents as migration routes. Currents such as the West Greenland Current and the Labrador Current provide predictable flows of water rich in plankton. By following these currents, the birds conserve energy while moving through favorable feeding zones.

Using currents also helps the birds maintain direction. Although they do not rely solely on currents, these natural pathways form an important structural guide during long migrations.

Scientists studying little auks have discovered that their movements are highly synchronized with the distribution of prey carried along these currents. The birds adjust their positions according to changes in oceanographic patterns each year.

Sunlight, stars, and magnetic fields

Little auks possess excellent navigational instincts. Like many migratory birds, they likely use a combination of sunlight orientation and geomagnetic signals. Their ability to sense Earth’s magnetic field helps them maintain direction even in cloudy weather.

During spring and summer, when daylight is continuous, they may rely more on solar cues. In low light or nighttime, they can use stars to adjust their route. These natural navigation tools allow them to travel across open ocean without visible landmarks.

This remarkable internal navigation system ensures they return to the same areas year after year. Many individuals likely follow inherited migratory paths passed down through generations.

Group migration and communication

Little auks migrate in large flocks, sometimes forming thousands of birds moving together in coordinated patterns. Group travel offers several advantages. The birds benefit from shared information about wind direction, foraging areas, and predator presence.

Flocks help individuals maintain stable flight paths. Flying in groups also reduces energy expenditure, as birds may use the air vortices created by their neighbors. Coordinated movement increases overall success during long migrations.

Communication plays an important role in keeping flocks together. Little auks produce distinctive calls that allow individuals to locate one another during flight or on the water. These vocal signals strengthen social bonds and enhance navigation.

Key Migration Routes of the Little Auk

The west Atlantic route

Many little auks migrate from Greenland and Arctic Canada toward the Labrador Sea and western North Atlantic. This route leads them into waters near Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, where cold currents create rich feeding grounds.

During winter, these birds move between the Labrador Current and open waters farther south. They remain in these areas until spring before returning north along similar paths.

This migration corridor supports massive flocks and is one of the most important routes for the species. Oceanographic stability makes it a reliable wintering area.

The east Atlantic route

Little auks breeding in Svalbard, Franz Josef Land, and northern Russia travel into the Barents Sea region. From there, they disperse into waters near Norway, Iceland, and the Greenland Sea.

These areas offer diverse wintering opportunities influenced by the North Atlantic Drift, which keeps waters relatively ice free. The mixing of cold and warm currents supports abundant plankton, making it ideal for feeding throughout the winter months.

These birds may shift positions throughout the season based on storms, food distribution, and temperature changes.

Occasional movements into the North Sea

Although less common, little auks sometimes move into the North Sea during harsh winters. Storms and unusual wind patterns may push flocks into more southern waters. These events often lead to large numbers of little auks being observed along European coastlines.

Such movements highlight the impact of weather on migration patterns. The North Sea does not typically support large overwintering populations, but it becomes a temporary refuge when conditions elsewhere change rapidly.

How Climate Change Affects Little Auk Migration

Shifting sea ice patterns

Climate change is altering sea ice distribution across the Arctic. Earlier melting and delayed freezing shift the timing of food availability. These changes affect little auk breeding, chick survival, and migration timing.

If sea ice retreats too rapidly, the plankton bloom timing may shift. A mismatch between peak plankton abundance and chick feeding needs could reduce breeding success. As a result, little auks may adjust their migration patterns in response to climate-driven changes in marine productivity.

Warming oceans and prey distribution

Warmer water temperatures influence the distribution of copepods and other zooplankton. Some prey species may move deeper or shift northward, forcing little auks to adjust their traditional routes.

If prey becomes less predictable, little auks may travel longer distances to find food. These shifts could increase energy expenditure during migration and reduce survival rates.

Long-term changes in ocean ecosystems may reshape migration routes and wintering areas. The impact of these shifts remains a focus of ongoing research.

Increased storm frequency

Stronger and more frequent winter storms influence little auk migration by disrupting feeding grounds and altering sea conditions. Birds may become displaced or forced into less favorable areas.

Extreme weather events can lead to mass strandings or mortality along coastlines. These events highlight the vulnerability of small seabirds to climate instabilities.

The Remarkable Endurance of Little Auk Migration

Energy demands and feeding strategies

Migration requires enormous amounts of energy. Little auks must accumulate fat reserves during late summer to fuel their journey. Once at sea, they rely on abundant zooplankton to maintain strength.

Their feeding strategy involves repeated dives to capture small prey. These dives may last several seconds and reach considerable depths. The birds alternate between flying, resting on the water, and diving for food. This pattern conserves energy and sustains them throughout migration.

The birds’ metabolism is finely tuned for cold-water environments. These physiological traits allow little auks to maintain body temperature and energy levels during harsh winter conditions.

Flock coordination and safety

Traveling in flocks helps little auks avoid predators such as skuas, gulls, and Arctic foxes. Safety in numbers gives the birds a greater chance of survival. Flocks also provide stability during migration, reducing the risk of individuals becoming lost.

Flocking behavior enhances navigation, feeding efficiency, and social cohesion. It remains one of the most important survival strategies for the species.

Returning to the same sites each year

Little auks exhibit strong site fidelity. They return to the same breeding colonies and often the same wintering areas year after year. This consistency depends on accurate navigation, environmental memory, and inherited migration behaviors.

Returning to familiar areas reduces uncertainty. The birds know where food is likely to be found and where conditions remain favorable. This stability enhances long-term survival across generations.

FAQs About Little Auk Migration

Why do little auks migrate so far?

They migrate long distances to reach winter feeding grounds with abundant zooplankton and open water.

When do little auks migrate?

Migration typically begins in late summer or early autumn, depending on ice formation and food availability.

How far do little auks travel?

Some populations travel thousands of kilometers between breeding and wintering areas in the North Atlantic.

Do little auks migrate alone or in groups?

They migrate in large flocks, which helps with navigation and protection from predators.

What triggers their migration?

Changes in daylight, sea ice expansion, and declining food availability trigger their movement.

Do all little auks follow the same route?

No. Migration routes vary by colony location and environmental conditions.

Where do little auks spend winter?

They winter in the North Atlantic, especially around Iceland, Greenland, Norway, and Newfoundland.

Are little auks affected by climate change?

Yes. Shifts in sea ice and ocean temperature influence food availability and migration timing.

How do little auks find their way?

They use a combination of magnetic navigation, solar position, ocean currents, and flock coordination.

Do storms affect migration?

Strong storms can displace birds and push them into unfamiliar waters, sometimes leading to strandings.

Final Thoughts

The migration of the little auk stands as one of nature’s most extraordinary achievements. These tiny seabirds travel immense distances across the North Atlantic to survive seasonal shifts in food availability, daylight, and marine conditions. Their journey reflects a powerful connection between Arctic ecosystems and the broader ocean environment.

Despite their small size, little auks demonstrate remarkable endurance and navigation skills. Their ability to adapt to changing seasons and challenging conditions highlights the resilience of seabirds in northern waters. As climate change alters marine ecosystems, understanding little auk migration becomes more important than ever.

Watching these birds glide across frigid seas or return to their breeding colonies each spring is a reminder of the intricate balance that governs the natural world. Their migration tells a story of survival, instinct, and the enduring power of life in the Arctic realm.