In the heart of forests, meadows, and open woodlands across North America, wild turkeys live out one of nature’s most compelling stories. From the moment a hen quietly lays her first egg in a hidden nest, to the day a full-grown tom struts under the spring sun with tail feathers fanned, every stage in a wild turkey’s life is a lesson in survival, growth, and instinct.

Far from being just a familiar figure in fall folklore, the wild turkey is a sophisticated bird with complex behaviors, razor-sharp senses, and a remarkable life cycle that few get to witness closely. In this in-depth guide, we’ll explore the journey of a wild turkey from egg to adulthood—revealing how fragile beginnings transform into formidable maturity.

From the Start: Where Life Begins

Nesting on the Ground: A Bold Strategy Hidden in Plain Sight

While many birds seek the safety of tree branches for nesting, the wild turkey takes a different—and riskier—path. Instead of building high, the turkey hen chooses to nest at ground level, often in dense vegetation, beneath thickets, or along the edge of a quiet woodland clearing. She creates a shallow hollow in the earth, padding it carefully with dry leaves, twigs, and grass. The result is a nest so well-camouflaged that even experienced predators may pass it by without notice.

At first, this ground-level approach seems dangerously exposed. And in some ways, it is. Raccoons, snakes, foxes, and sudden storms all pose serious threats. Yet there’s a calculated wisdom in this choice. Rather than relying on distance from the ground, the hen relies on stillness and stealth. She remains motionless for hours, becoming part of the forest floor itself—her feathers blending into the dappled light and leaf litter.

This quiet vigilance is not just instinct; it’s survival strategy honed by generations of successful mothers who knew how to vanish without a trace.

The Art of Timing: Egg Laying and Incubation

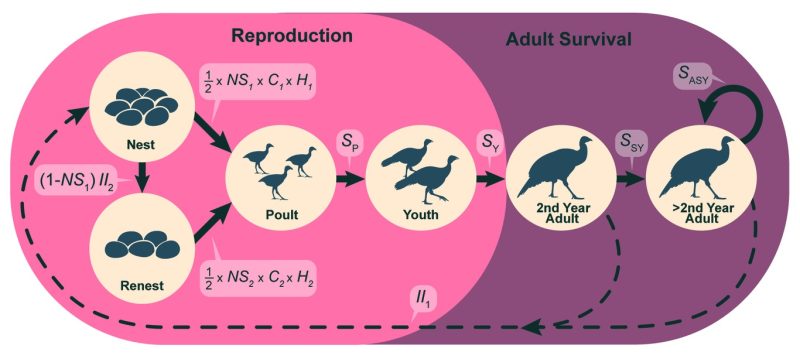

Once she has chosen her nest site, the hen begins to lay—one egg per day, typically in the soft light of morning. Over the course of 10 to 14 days, she gradually builds a full clutch. But in a remarkable act of biological precision, she does not begin incubating immediately. Instead, she waits until the last egg is laid, ensuring that all embryos start developing at the same time.

This synchrony matters. When the eggs finally hatch, the poults emerge together, equally strong, equally ready. There are no stragglers—only a tightly bonded brood that can move with their mother from the very start.

Incubation itself is a quiet test of endurance. For nearly a month—26 to 28 days—the hen sits alone, exposed to weather, danger, and hunger. She leaves the nest only briefly and rarely, risking her own safety to nourish herself just enough to keep going. Her body becomes the eggs’ only source of warmth, and her presence their shield.

In this vulnerable silence, a new generation of wild turkeys is already forming—hidden beneath feathers, warmed by devotion, and timed perfectly for the moment they must face the world.

Hatching: A Struggle Worth Surviving

Breaking Out of the Egg: The First Test of Strength

Hatching is not a dramatic, sudden moment—it’s a long, grueling rite of passage. As the time nears, the tiny chick inside the egg begins to stir, pushing gently against the inner shell with its beak. At the tip of that beak is a temporary, sharp projection known as the egg tooth—a tool nature provides for just this occasion.

With rhythmic taps and tiny bursts of effort, the poult slowly chips away at the shell from within. Each motion is deliberate, each pause a moment to rest and gather strength. The process can take up to 24 hours, and for much of that time, it looks as if nothing is happening at all.

But inside, everything is changing.

This exhausting struggle is more than a way out—it’s the chick’s first workout. The resistance of the shell forces the developing muscles in its neck, wings, and legs to engage. Without this effort, it would not have the strength to stand, walk, or follow its mother in the hours ahead.

By the time the poult finally breaks free—damp, exhausted, but breathing the outside air—it has already proven its will to survive. Before it takes its first step, it has already passed its first great challenge.

First Hours: Up and Moving

The moment a wild turkey poult breaks free from its shell, it enters the world not as a helpless newborn, but as a remarkably capable little creature. Unlike songbirds that hatch naked, blind, and dependent, turkey poults are precocial—born fully alert, with their eyes wide open and bodies cloaked in soft, insulating down.

Within just a few hours, they are already on their feet, wobbling but determined, instinctively drawn to the sound and warmth of their mother. They don’t wait days to become mobile—they must move quickly. The ground may be where life begins, but it’s also a dangerous place, teeming with predators that can track the scent of a fresh hatch.

Precocial development is nature’s solution to this risk. These poults are designed to follow. Their strong legs carry them in tight formation behind the hen as she leads them away from the nest and into a world filled with both danger and opportunity.

In their very first hours, these tiny birds are already practicing survival—staying close, staying alert, and taking their first steps in a life that demands awareness from the start.

The Poult Stage: Growing Fast and Learning Even Faster

The Race Against Predators

The first two weeks of life are a constant test of speed, instinct, and luck. Newly hatched turkey poults are small, soft, and silent—perfect prey for a long list of predators. Hawks scan from above. Foxes and snakes move silently through the underbrush. Even a sudden summer storm can be fatal. At this stage, survival hinges on one thing: growing up fast.

And they do. Fueled by a diet rich in insects—beetles, grasshoppers, spiders—poults pack on strength and feathers at an astonishing rate. Protein is their secret weapon. Every bug they catch builds the muscles they’ll need to run, leap, and eventually fly.

But they don’t face these challenges alone. The mother hen is more than a protector—she’s a teacher. With a quiet cluck, she tells her brood to freeze in place, vanishing into stillness when danger is near. A different call sends them scurrying to regroup under cover. Her signals are subtle, but the poults learn quickly. Their lives depend on it.

In this early chapter, nature offers no second chances. For a young turkey, survival is a race—and every step, every bite, every lesson counts.

The Role of Senses in Early Survival

In a world where hesitation can mean death, wild turkey poults are born with more than just legs to run—they come equipped with some of the sharpest senses in the bird world. Though barely a day old, their eyesight is remarkably acute, capable of detecting the slightest flicker of motion in the grass or the shadow of a hawk overhead. Their wide-set eyes give them a broad field of view, allowing them to spot threats from nearly every angle.

Just as vital is their keen sense of hearing. From their very first hours, poults can pick up the subtle vocal cues of their mother—soft clucks, urgent warnings, and guiding calls—each one carrying precise meaning. A single note might mean “freeze,” another “move now,” and they respond without question.

These finely tuned senses aren’t just helpful—they’re essential. In dense vegetation, where predators hide in silence, seeing and hearing can make the difference between life and a silent disappearance. Nature has little room for error, and so it arms these fragile, fast-growing birds with the sensory tools they need to stay one step ahead.

Before they can even fly, wild turkey poults are already reading the world like survivors.

First Flights: A Lifesaving Skill

For a wild turkey poult, flight isn’t just a milestone—it’s a matter of survival. Around day 10, their wing feathers begin to push through, transforming fluffy down into structured tools for escape. By the third week, those wings are strong enough to lift them off the forest floor, even if only for a few fleeting seconds.

But those few seconds are everything.

With a burst of energy, a young turkey can launch itself into low branches, where it is far safer than on the ground below. Nightfall brings new dangers—coyotes, raccoons, foxes—and the forest floor becomes a hunting ground. To roost just a few feet above that danger is to gain a critical advantage in the race to adulthood.

These first awkward flights mark a turning point. With each leap into the branches, poults become more agile, more confident. And though they are still small, still learning, they are no longer helpless. In the wild, even a few inches off the ground can mean the difference between life and death.

Molting and Feather Development

Growth for a wild turkey isn’t just about getting bigger—it’s about transformation. As poults mature, their soft, fuzzy down begins to fall away, replaced by the first layers of structured juvenile feathers. This molting process marks a critical shift: from fragile fluff to the aerodynamic tools of a bird built for flight, camouflage, and survival.

The new feathers offer more than just warmth. They’re shaped to catch the air, improve balance in flight, and help the bird blend into its surroundings. At this stage, camouflage is still key. The developing plumage carries earthy tones that echo the forest floor—browns, tans, and mottled patterns that make young turkeys almost invisible in dappled light.

As the months pass and adulthood nears, another transformation takes place. Males begin to shine—literally. Their feathers shift into deep bronzes, coppers, and iridescent greens that shimmer in sunlight. These vibrant colors are more than decoration; they’re a signal of health, strength, and readiness to compete for mates.

Females, by contrast, retain muted, understated hues—an evolutionary choice. Their job will be to nest quietly, undetected, often in the same vulnerable ground cover where they once hatched. Their camouflage remains a powerful tool not just for self-preservation, but for the safety of future generations.

In wild turkeys, feathers are not just for flying—they are survival, identity, and strategy, all written in color and form.

Juvenile Stage: Gaining Independence

Forming Flocks and Finding Their Place

By five to six weeks of age, poults start to resemble young adults. They form flocks with their siblings and mother, and begin to establish social hierarchies. Young males often practice strutting and light sparring, early signs of dominance behavior that will define adult interactions.

Their diet now includes more seeds, berries, and greens as they become less dependent on protein-rich insects. Their digestive system gradually shifts to accommodate an adult diet.

Communication and Social Intelligence

Turkeys are among the most social birds in the wild. Even as juveniles, they use a wide range of vocalizations—chirps, purrs, yelps, and clucks—to communicate. Each sound has a distinct meaning: warning, reassurance, alarm, or a call to regroup. Body posture, feather position, and even eye contact all play a role in their complex social language.

Adult Stage: Strength, Identity, and Mating

Physical Maturity and Sexual Differences

By four to five months, turkeys are nearly full-sized. Males, now called jakes, develop longer legs, brighter feathers, and start growing a beard—a cluster of coarse bristles from their chest. Females, or jennies, remain smaller and plainer in coloration.

They may look grown, but they typically don’t breed until their first spring, roughly 10 months after hatching.

Mating Displays and Territory

As spring arrives, mature males—known as toms—become territorial and begin elaborate courtship displays. These include puffing up their bodies, fanning out their tail feathers, dragging their wings, and gobbling loudly. These displays are meant to impress hens and signal dominance over rival males.

Hens carefully observe these behaviors, selecting mates based on appearance, sound, and confidence—traits that signal strong genes for the next generation.

Seasonal Hormone Shifts and Reproductive Cycles

Turkeys are deeply connected to seasonal rhythms. Increasing daylight in spring stimulates hormonal changes that drive mating behavior. Males become more aggressive and vocal, while females prepare to nest. This synchronization ensures that poults will hatch during warm months when food is plentiful and conditions are favorable for survival.

Environmental Pressures and Mortality Rates

Why So Few Make It to Adulthood

Despite their adaptations, turkeys face intense environmental pressure. Predation, disease, harsh weather, and habitat loss all reduce survival rates. Less than 30% of poults make it to adulthood. Hens lay large clutches not because all will survive, but because few will—and nature plays the odds.

Seasonal Behavior and Lifespan

Adapting to the Seasons

Wild turkeys don’t migrate, but they adjust their behavior with the seasons. In autumn, they form larger flocks, often grouped by age and sex. In winter, they rely on acorns, nuts, and grains, using body fat and communal roosting to survive cold temperatures.

As spring returns, flocks break apart for the breeding season, and the life cycle begins anew.

How Long Do They Live?

In ideal conditions, wild turkeys can live up to 10 years, but most live only three to five years in the wild. The early stages of life are the most dangerous, but those who survive become intelligent, alert, and remarkably adaptable birds.

Conclusion: A Life of Survival and Strategy

From a well-camouflaged egg in a forest nest to a proud adult turkey strutting beneath the spring sky, the journey of a wild turkey is one of risk, instinct, and evolution. Each stage—each choice, each adaptation—is shaped by millions of years of survival.

Understanding this life cycle helps us see wild turkeys not just as wildlife, but as strategic survivors in a challenging world. And in every poult that takes its first flight, or tom that gobbles into the morning air, nature’s story continues—resilient, rhythmic, and remarkably wild.