Cranes are among the tallest, most elegant birds on Earth, admired for their graceful courtship dances and long migratory journeys. Found across wetlands, prairies, and grasslands in Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas, these birds belong to the family Gruidae and have life cycles that reflect their intelligence, longevity, and strong pair bonds. This article explores the life cycle of cranes—from courtship and egg laying to adulthood and migration—highlighting what makes them both biologically fascinating and ecologically important.

Overview of the Crane Life Cycle

The life cycle of a crane is a remarkable journey of transformation, rooted in instinct, guided by seasons, and shaped by the landscape. From a dazzling dance in the marsh to soaring migrations across continents, each phase in the crane’s life is as purposeful as it is elegant.

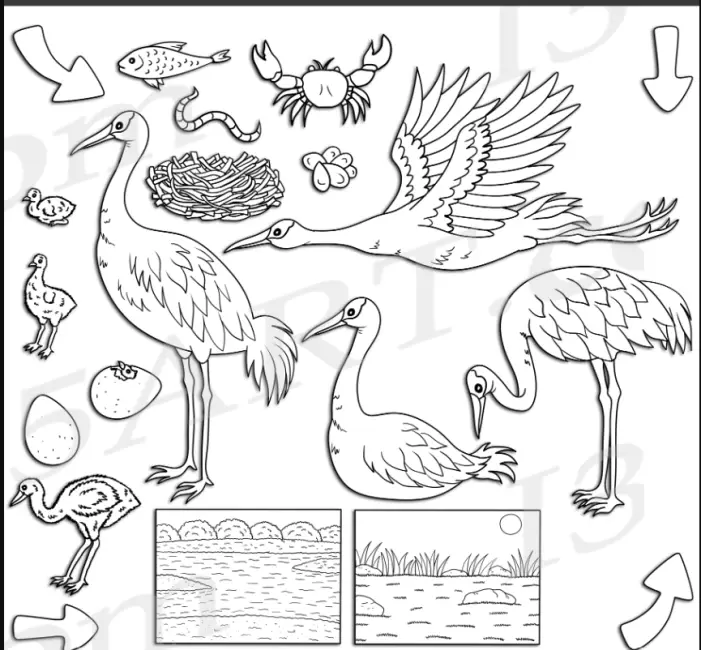

This cycle unfolds across six major stages, each reflecting a different dimension of survival, learning, and legacy:

-

Courtship and Pair Formation – where lifelong bonds begin with complex dances and synchronized calls.

-

Nesting and Egg Laying – the delicate beginning of new life, hidden within reeds and wetlands.

-

Incubation – a time of stillness and protection, as parents take turns warming and guarding the future.

-

Hatching – when fragile colts break into the world, ready to walk within hours of birth.

-

Chick Development (Colt Stage) – a period of rapid growth, where the young learn to forage, follow, and mimic.

-

Fledging, Independence, and Adulthood – the transformation into graceful fliers and, eventually, devoted parents themselves.

Each stage is finely tuned to the timing of the seasons, the ecology of wetlands and prairies, and the unique behaviors of each crane species. Whether it’s the widely distributed Sandhill Crane (Antigone canadensis) or the endangered and majestic Whooping Crane (Grus americana), every crane’s life follows this ancient rhythm—a rhythm passed down through sky and marsh for millions of years.

Courtship and Pair Formation

Dances That Bond for Life

Few scenes in the natural world are as captivating as the sight of two cranes engaged in their intricate courtship ritual. Before a single egg is laid or a nest is built, the crane’s life cycle begins with a performance of devotion and rhythm—a dance that transcends mere survival and enters the realm of ritual and bonding.

Cranes are monogamous by nature, and many species form lifelong pair bonds. This fidelity is rooted not just in biology but in a process of mutual selection and communication. The courtship dance—often observed in open marshes or grasslands—is both a test of compatibility and a strengthening of emotional connection.

The dance itself is a choreographed display of grace and energy. Males and females leap high into the air, toss grasses or sticks, and perform synchronized wing-flapping, head-bobbing, and trumpet-like calls that echo across the wetland. These movements are not competitive but collaborative, expressing alignment, vitality, and readiness to breed.

Young or unpaired cranes, especially first-time breeders, engage in these displays to find a mate, while long-established pairs repeat them each season to renew their bond. It is not unusual to see mated cranes dancing well beyond the breeding season—proof that their rituals are about more than reproduction; they are about connection and loyalty.

Timing and Territory

Pair formation usually begins in late winter or early spring, sometimes before the birds have even reached their nesting grounds. In migratory species like the Sandhill Crane, these dances may occur in staging areas—rest stops along migration routes where large groups of cranes gather. In non-migratory or resident populations, pair bonding often takes place in established territories, where food and nesting materials are already being scouted.

Once a pair has formed or reaffirmed their bond, they begin searching for a nest site, often returning to locations where they have successfully bred in past years. From this point on, the cranes move forward not just as individuals, but as a unified team, preparing to raise the next generation.

Nesting and Egg Laying

Choosing the Right Site: A Balance Between Safety and Resources

Once the courtship dance has sealed their bond, the mated crane pair turns their focus to the next critical step in the life cycle: choosing a nest site. This decision is not made lightly—it is a delicate balance between protection from predators, proximity to food, and access to water.

Most cranes prefer to nest in shallow wetlands, grassy marshes, or reedy lake edges, where visibility is high and water provides a natural moat. These habitats also support an abundance of insects, amphibians, and aquatic plants—the first meals for their future chicks. Nesting in waterlogged areas helps discourage land predators such as foxes, raccoons, or feral dogs from approaching undetected.

Different species show distinct preferences. For example, the Wattled Crane (Bugeranus carunculatus) seeks out remote, undisturbed wetlands, sometimes miles from human presence. Meanwhile, the adaptable Sandhill Crane (Antigone canadensis) may nest in open prairies, agricultural fields, or even suburban wetlands, provided there is enough cover and food nearby.

Nest Construction: A Platform for New Life

Once a suitable site is chosen, the pair works together to build the nest—a process that may take several days. The nest is a shallow mound or platform, typically 30 to 60 centimeters wide, composed of nearby plant material such as reeds, sedges, grasses, and mosses. It may be built directly on floating vegetation, on a small island, or even atop a muskrat lodge.

Despite their large size, cranes are gentle nest builders, carefully layering materials with their long bills. The structure is sturdy enough to withstand wind and water movement, yet soft enough to cushion fragile eggs.

Egg Production: Two Chances for Survival

Most crane species lay two eggs per clutch, spaced one to two days apart. This spacing results in asynchronous hatching, which may affect chick survival if food is scarce. In the wild, it’s common for only one chick to fledge successfully, as sibling competition, limited resources, or predation often prevent the weaker chick from surviving.

The eggs themselves are olive-brown to buff-colored, often blotched with darker markings that provide natural camouflage among reeds and grasses. Each egg weighs around 130 to 160 grams, depending on the species—a significant investment of energy and resources by the female.

Once laid, the eggs represent the future of the species, cradled in silence as the parents begin the next phase of devoted care: incubation.

Incubation: A Shared Task

Keeping the Future Warm

Once the eggs are laid, the crane’s role shifts from builder to guardian. For the next 28 to 32 days, depending on the species, both parents devote themselves to the critical task of incubation—keeping their fragile cargo warm, protected, and alive.

Unlike many bird species where incubation falls solely to the female, cranes exhibit a remarkable level of parental equality. Male and female take turns sitting on the nest, with smooth transitions occurring throughout the day. One adult may take a brief flight to feed or stretch, while the other immediately takes its place, ensuring the eggs are never left uncovered for long.

To support healthy embryonic development, the incubating parent turns the eggs several times a day using its beak or feet. This subtle movement promotes even warmth, prevents the embryo from sticking to the shell, and helps align the chick into the proper hatching position as the final days approach.

Ever-Vigilant Watchers

But incubation is far from peaceful. In the wild, crane nests are often exposed to the elements and visible to predators. Raccoons, foxes, coyotes, crows, ravens, and even large birds of prey pose constant threats to unattended or poorly hidden eggs. In many crane habitats, especially open marshes or prairie wetlands, camouflage alone is not enough.

To counter these dangers, cranes rely on a combination of:

-

Nest placement, often over water or in isolated areas

-

Cryptically colored eggs, blending in with grasses and reeds

-

Aggressive nest defense, including loud alarm calls, threat displays, and even physical attacks on intruders

A startled crane may appear calm and elegant in flight, but when defending its nest, it becomes a formidable force—striking with powerful bills and loud calls that ripple across the wetland.

Patience and Persistence

The incubation period is long and demanding. Through rain, heat, or wind, the parents remain steadfast. Their dedication is a testament to the species’ evolutionary success—carefully balancing risk and resilience, stillness and vigilance.

At the end of this quiet, watchful period, a faint tapping begins inside the shell. The next stage of the crane’s life cycle—hatching—is ready to unfold.

Hatching: A Delicate Emergence

From Shell to Sunlight

After nearly a month of warmth, vigilance, and silent growth inside the egg, a quiet but powerful process begins: hatching. From within the egg, the crane chick begins to stir. Its body has been preparing for days, absorbing the remaining yolk and shifting into position. Now, it’s time to meet the world.

The first sign of life is a tiny crack in the shell, made by the chick’s egg tooth—a temporary, pointed structure on the beak used solely for this purpose. This process, called pipping, is slow and exhausting. The chick doesn’t break the shell in one go; instead, it chips away methodically, forming a ring around the inside of the shell known as the star-shaped fracture line.

The entire ordeal can take 12 to 24 hours, sometimes longer, and is rarely assisted by the parents. Instead, the adults remain close, vocalizing softly, responding to faint peeps from inside the egg—a moment of communication even before the chick is born.

Finally, with one last heave, the chick pushes free—wet, blinking, and alive. The once-silent nest now holds a new voice, small but insistent, calling out beneath the watchful gaze of its parents.

Born Ready, But Not Alone

Unlike many birds that hatch blind, helpless, and featherless, crane chicks are precocial—highly developed at birth. Covered in golden or brown down, with eyes wide open and legs already strong, they are ready to stand within hours of hatching and can walk, follow, and vocalize on their first day.

But readiness is not independence.

Despite their mobility, crane chicks remain deeply dependent on their parents. They rely on them for:

-

Thermal regulation in cold or rainy weather

-

Feeding, as they learn to forage by mimicking parental movements

-

Protection, since predators are most dangerous in these early days

One adult often leads the chick through its first steps outside the nest while the other stands guard, scanning for any sign of danger. These first days are crucial: a time of bonding, learning, and survival, where every moment is a delicate dance between vulnerability and instinct.

Chick Development: The Colt Stage

Growing Strong on the Marsh

The moment a crane chick hatches, it enters a world filled with motion, sound, and survival—and it doesn’t face it alone. These downy young birds, known as colts, waste no time embracing the world outside the shell. Within hours of hatching, they are already up on their long, unsteady legs, stumbling behind their parents in the shallow waters of the marsh.

Colts are born with a basic instinct to follow, but everything else must be learned—and quickly. For the first several weeks of life, crane chicks learn by watching, closely mimicking their parents’ every move. From foraging techniques to predator avoidance, their education is visual, constant, and essential.

Feeding, Growth, and Transformation

In these early days, food is delivered directly by the parents—tiny morsels of insects, snails, aquatic invertebrates, and soft green shoots, carefully selected and offered from bill to bill. The diet is high in protein and moisture, designed to fuel one of the fastest growth rates in the bird world.

As days pass, the transformation is striking:

-

The colts’ legs and necks elongate, strengthening to support balance and deeper wading.

-

Their soft, golden down begins to give way to juvenile plumage, as small feathers emerge from sheathed pinfeathers along the wings and body.

-

Their coordination improves daily, and soon they’re pecking at insects on their own, imitating their parents’ foraging patterns with increasing accuracy.

Crane parents remain extremely vigilant during this stage. Every rustle in the reeds, every shadow overhead is met with alert calls or defensive posturing. The family unit functions as a tight, mobile team, gliding silently through the wetlands with the colts tucked safely between the towering legs of their guardians.

Milestone at Ten Weeks

By the time a colt reaches 10 weeks of age, it has undergone a dramatic transformation. The once-fluffy chick has grown nearly three times its original size, with strong, scaled legs and growing primary feathers. However, while they may appear almost adult-like in stature, colts are still flightless. Their flight muscles are developing, their wings are not yet fully formed, and their reliance on parents—though reduced—remains crucial.

This stage is one of mobility without escape, making colts especially vulnerable to predators like raccoons, snapping turtles, hawks, and even larger wading birds. Constant vigilance and good habitat cover are essential to their survival until they reach the next milestone: fledging—the moment they finally take to the skies.

Fledging and Learning to Fly

First Flights into the Skies

For weeks, the young crane—now nearly the size of its parents—has been running across wetlands, flapping its growing wings, and strengthening the flight muscles that will soon lift it into the air. Then, somewhere between 70 to 100 days of age, depending on species, habitat, and nutrition, comes one of the most transformative moments in a crane’s life: fledging.

The first true flight is not effortless. The young crane must launch its tall, still-growing body into the air, coordinate long legs and broad wings, and stay airborne with control. These first flights are often short and clumsy—a few wingbeats over the marsh, followed by an unsteady landing—but they signal the beginning of independence.

Fledging marks more than just a physical milestone. It is a psychological shift: the chick is no longer earthbound, and it can now follow its parents into new feeding grounds, escape predators with speed, and begin rehearsing for migration.

Family Bonds After Flight

Even though it can now fly, the juvenile crane does not immediately leave its parents. Cranes are highly social and family-oriented, and young birds remain under parental care well beyond the fledging stage. The family unit continues to move together as a coordinated trio, with the juvenile shadowing its parents’ movements across wetlands, upland fields, or along shallow riverbeds.

This extended period of post-fledging learning is crucial. During this time, the young crane gains:

-

Advanced foraging skills, including how to dig for tubers, capture frogs, or spot hidden insects

-

Threat recognition, learning to distinguish predators and react appropriately

-

Social communication, through vocalizations, body language, and even dance

-

And most importantly, orientation and navigation skills for migration

Preparing for the First Migration

As autumn approaches, the family prepares for one of the most demanding challenges in the crane’s life: migration. For species like the Sandhill Crane and Whooping Crane, this journey may stretch hundreds or even thousands of miles to reach overwintering grounds in warmer regions.

Young cranes do not instinctively know the route. Instead, they learn by following their parents, imprinting on the visual landmarks, stopover sites, and flock dynamics that will guide them for years to come. These first migratory journeys are as much about bonding and learning as they are about survival.

By the time the juvenile completes its first round trip—returning the following spring to its natal region—it will have passed the greatest test of its early life. Now equipped with the skills of flight, foraging, and orientation, it stands on the edge of the next stage: adulthood.

Adulthood: Maturity and Breeding Readiness

A Long Road to Reproduction

Though they hatch walking and grow quickly in their first months, cranes take their time reaching reproductive maturity. Most species do not breed until they are three to five years old, making cranes some of the slowest-maturing birds among large avian species. This extended adolescence is a period of preparation—not just physical, but social and behavioral.

Before forming lifelong bonds, young cranes spend their formative years in non-breeding flocks made up of other subadults. These groups roam widely through foraging grounds, rest at communal roosts, and observe the rituals of older pairs. It is during this time that juveniles practice their dance displays, vocal duets, and territorial behaviors, refining the complex skills that will later secure a mate.

This developmental phase also allows young cranes to scout future nesting territories, sometimes returning season after season to the same general area. Their choices are informed by landscape memory and social learning—a combination of instinct and experience.

Longevity and Stability

Cranes are built for the long game. In the wild, a healthy crane may live 15 to 25 years, depending on the species and environmental pressures. Under human care, or in protected reserves, some individuals have surpassed 30 years of age, making cranes among the longest-lived wild birds.

Their slow maturity is balanced by this long lifespan, and by a low but stable reproductive rate. Unlike songbirds that raise many chicks per season, cranes focus on quality over quantity—raising one or two colts at a time, but often returning to breed for two decades or more.

Completing the Circle

Once sexually mature, cranes seek mates and form bonds—often during late winter or early spring. Many return to the very wetlands or grasslands where they themselves were raised, a behavior known as philopatry. Familiar with the land and its seasonal rhythms, they begin the nesting process with the advantage of memory and home-ground knowledge.

Their first successful breeding marks not just a biological milestone, but a full-circle return to the beginning of the life cycle. The adult crane—once a colt learning to walk—now performs the same dances, builds the same nests, and raises new life among the reeds and sky.

Migration: The Final Seasonal Chapter

Traveling with the Flock

As summer fades and northern marshes begin to cool, cranes prepare for one of the most awe-inspiring spectacles in the bird world—migration. For many crane species, especially those living in temperate climates, migration is not just a seasonal journey but a deeply embedded, biologically timed rite of passage.

Each autumn, flocks rise into the skies in long, elegant formations, their calls echoing over fields and river valleys. These aren’t random wanderings. Cranes follow ancient migratory flyways—well-established aerial highways that stretch across continents, connecting breeding grounds in the north to overwintering habitats in the south. The routes are remarkably consistent year after year and often span thousands of kilometers.

For example, the Whooping Crane (Grus americana) and Sandhill Crane (Antigone canadensis) migrate across North America, traveling from Canada and the northern U.S. to wetlands in Texas, Florida, and Mexico. Along the way, they stop at vital staging areas—wetlands and plains where they rest, refuel, and gather in large social groups.

Learning the Sky: A Family Affair

One of the most remarkable aspects of crane migration is that it is learned, not instinctive. Juvenile cranes do not simply know where to go—they learn the routes by following their parents. Each bend in the river, each feeding site, each safe roosting spot is passed down generationally through flight. Without this guidance, many young cranes would become lost or perish.

This knowledge transfer highlights the importance of family cohesion even after fledging. The young birds continue to benefit from the experience of their parents through the entire migratory cycle, only joining mixed-age flocks after their first winter.

More Than a Journey

Migration is not simply movement—it is an essential survival strategy tied to the crane’s biology. These long journeys are carefully timed with:

-

Shifting climate patterns, to avoid freezing wetlands

-

Food availability, such as grains, invertebrates, and aquatic vegetation

-

Reproductive schedules, ensuring they return to breeding sites as the habitat peaks in fertility

Migration is also physically demanding. Cranes must navigate wind patterns, weather fronts, and habitat loss along their flyways. Yet, year after year, they persist—guided by memory, magnetic fields, and the pull of ancestral places.

For cranes, migration is the final seasonal chapter—one that brings the life cycle full circle. As they return to the breeding grounds in spring, often to the exact marsh or field where they were born, they begin the cycle anew, dancing once again in the sunrise.

Conclusion: A Life Shaped by Devotion and Flight

The life cycle of a crane is a story of loyalty, learning, and long-distance endurance. From their deep pair bonds and elaborate dances to their precise parenting and migratory legacy, cranes embody a rare balance of grace and resilience.

Their slow, deliberate growth and long lifespans stand in contrast to many fast-breeding birds, reflecting an evolutionary investment in quality over quantity. Understanding the crane’s life cycle not only highlights their beauty but underscores the importance of preserving their wetlands and flyways—the landscapes that cradle each stage of their journey.