Few creatures stir primal fear like sharks. The mere sight of a fin slicing through ocean waves has inspired centuries of legends, tabloid headlines, and blockbuster films. But what is it about these ancient fish that terrifies us more than nearly any other marine animal?

Sharks have been patrolling the oceans for over 400 million years, surviving mass extinctions and evolving into a wide array of highly specialized predators. Their reputation for power, stealth, and lethal precision has made them the ultimate symbol of danger beneath the waves. But is their fearsome status deserved—or misunderstood?

In this article, we’ll dive into the biology, behavior, and psychology behind why sharks are the ocean’s most feared predator, and explore what sets them apart from all others.

A Look at Shark Evolution: Predators From the Dawn of Time

Sharks have existed long before the dinosaurs, making them some of the oldest vertebrates still alive today. Their basic body plan—streamlined shape, cartilage skeleton, and replaceable teeth—has barely changed over hundreds of millions of years. Why? Because it works.

These evolutionary survivors have adapted to nearly every ocean habitat, from shallow coral reefs to the dark abyss of the deep sea. More than 500 species of sharks roam the world’s oceans, and while most are harmless to humans, a few have earned notoriety as apex predators capable of astonishing power and precision.

Their long evolutionary history gives them an air of primal terror—a sense that these creatures belong to a wilder, older world.

Key Features That Make Sharks Fearsome

A Jaw Full of Blades—And Thousands More on Standby

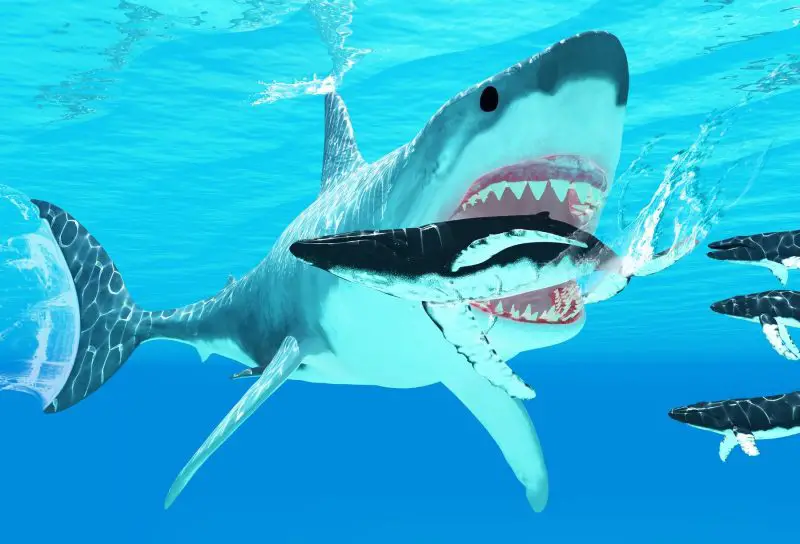

When it comes to nature’s deadliest tools, a shark’s mouth is unmatched. Lined with razor-sharp, serrated teeth, it’s not just a biting mechanism—it’s a flesh-shearing machine. But unlike most predators, sharks don’t settle for a single set of teeth. Instead, their jaws function like conveyor belts of destruction, constantly growing new teeth to replace old ones.

Over the course of a lifetime, some sharks may lose and regenerate up to 30,000 teeth. Whether it’s the triangular slicing knives of a great white or the needle-fine daggers of a tiger shark, each species carries a custom set of weapons, honed by evolution to grab, tear, and swallow prey with ruthless efficiency.

Supercharged Senses: Seeing the Invisible, Sensing the Unseen

Sharks experience the ocean in a way no land predator can imagine. While other animals rely on sight or scent alone, sharks are equipped with a full arsenal of specialized senses that elevate them to near-supernatural hunters.

-

Electroreception: Using tiny pores called ampullae of Lorenzini, sharks detect the electric fields emitted by living animals, even those buried beneath sand or hiding in complete darkness.

-

Olfactory dominance: Their sense of smell is so acute they can detect a single drop of blood in a million gallons of seawater—and then trace it for miles.

-

Vibration sensitivity: Sharks can feel the subtlest movements—the flailing of an injured fish, the thrum of swimming muscles—through lateral line systems that run along their bodies.

-

Panoramic vision: With eyes positioned on either side of the head, many sharks enjoy nearly 360-degree vision, giving them a constant watch for both prey and predators.

Together, these senses create a sixth-sense predator, capable of hunting in complete silence, darkness, or chaos.

Built for Speed, Ambush, and Ambiguity

Sharks are not chaotic killers—they’re calculated, tactical hunters. Species like the shortfin mako slice through the water at over 45 miles per hour, making them the fastest fish in the sea. The great white, perhaps the most iconic of all sharks, stalks from below and uses explosive bursts of speed to launch its 2-ton body out of the water, grabbing seals with bone-crushing power.

Their coloring—a shadowy gray top and pale white belly—provides counter-shading camouflage, rendering them nearly invisible from both above and below. Prey often doesn’t know the shark is there until it’s too late.

It’s not just strength that makes sharks deadly. It’s their ability to vanish into the sea, wait in total stillness, and then strike with precision honed by hundreds of millions of years of evolution.

The Psychology of Shark Fear

Why Do Sharks Scare Us More Than Other Predators?

Shark fear isn’t just about biology—it’s also psychological. Part of their terrifying mystique comes from their alien nature. Unlike marine mammals such as dolphins or whales, sharks show no facial expressions, vocalize nothing humans can hear, and seem emotionally unreadable.

Combine that with their ability to appear suddenly, from beneath murky water, and you have a perfect recipe for fear.

Hollywood’s Influence

Much of our fear is cultural. “Jaws” (1975) redefined public perception of sharks, portraying the great white as a vengeful, unstoppable killer. The film triggered a global wave of shark panic and, unfortunately, led to decades of misguided persecution.

Even today, headlines often amplify rare shark attacks, reinforcing the idea that they are lurking menaces—when in truth, you’re more likely to be struck by lightning or injured by a toaster than attacked by a shark.

Sharks vs. Other Ocean Predators

The ocean is home to many formidable hunters. Orcas strategize like wolf packs. Giant squid wrestle with whales in the abyss. Saltwater crocodiles patrol river mouths with prehistoric menace. Yet among all of these, no marine predator stirs fear in the human psyche quite like the shark.

So what makes sharks uniquely terrifying?

Unpredictable Appearances

While orcas follow migratory routes and crocodiles hug the brackish shallows, sharks can appear almost anywhere. From remote coral atolls to popular tourist beaches, their range is vast and their movements often invisible. This unpredictability taps into one of our most primal anxieties: the unseen danger beneath the surface.

Emotionless, Unreadable Presence

Unlike dolphins or orcas, sharks offer no facial expression, no vocal cues, no emotional feedback. They glide through the water with blank, black eyes, silent and unfazed. There’s no way to reason with a shark—no empathy, no signals of intent. To humans, this emotional opacity can feel more chilling than aggression itself.

Masters of Stealth

Sharks are specters of the sea, built for silence. They don’t splash, they don’t breach, they don’t roar. When a shark strikes, it often does so with no warning at all—a swift, silent lunge from below. Unlike crocodiles, which thrash violently, or orcas, which may herd prey to the surface, sharks often kill without a sound.

Evolutionary Precision

Sharks are the embodiment of evolutionary minimalism. Their bodies have barely changed in hundreds of millions of years because they are already perfect for the job. Streamlined, efficient, and specialized in every feature—from their teeth to their sixth sense for electrical fields—sharks are pure, unapologetic predation.

While orcas may be more intelligent and crocodiles more aggressive toward humans, sharks remain the iconic image of cold, instinctual efficiency. They do not hate, and they do not hesitate. That detachment—combined with their capability—makes sharks the symbol of fear in the sea.

Are Sharks Really That Dangerous?

Shark Attack Reality Check

For all the spine-chilling headlines and cinematic screams, the truth is this: shark attacks are incredibly rare. Globally, only 70 to 80 unprovoked attacks are reported each year. Of those, fewer than 10 result in death. Statistically speaking, you are far more likely to be struck by lightning, injured by a falling coconut, or even bitten by another human than attacked by a shark.

So why do we fear them so deeply?

Much of that fear comes from misunderstanding. In many cases, sharks mistake surfers and swimmers for prey—especially in murky water where a silhouette on the surface might resemble a seal or fish. These are not calculated, malicious strikes. They’re split-second errors made by an animal evolved to hunt in motion and shadow.

And most telling of all? After the first bite, sharks often let go and retreat—realizing they’ve made a mistake. A true predator hunting humans wouldn’t do that. Which is why marine biologists repeatedly emphasize: sharks do not view humans as prey.

In reality, many shark species are elusive and shy, actively avoiding people. The infamous great white? Difficult to study precisely because it vanishes the moment it senses human presence.

Our fear is real—but in many ways, it’s fear of the unknown, not the actual danger.

Threatened, Not Threatening

Ironically, while we paint sharks as ruthless killers, it is humanity that has become the apex predator in this relationship.

Every year, over 100 million sharks are killed—many for nothing more than their fins, sliced off and discarded in a gruesome practice known as finning. Others die as bycatch, tangled in fishing nets meant for tuna or swordfish. Some are hunted as trophies or for shark meat.

The result? Populations of many species—like hammerheads, oceanic whitetips, and even great whites—have plummeted, some by more than 90%. Species that once ruled the seas are now vanishing in silence.

But the loss of sharks isn’t just tragic—it’s ecologically catastrophic. As apex predators, sharks regulate the populations of other marine species. They keep prey fish from overgrazing seagrass beds and coral reefs, helping maintain the balance of entire ocean ecosystems. Remove the sharks, and the effects ripple outward: fisheries collapse, reefs degrade, and biodiversity unravels.

So are sharks dangerous?

Yes—to fish, seals, and sometimes to unlucky surfers. But the greater danger is not the shark in the water—it’s a world without sharks.

Conclusion

So, why are sharks the ocean’s most feared predator?

Because they are perfectly adapted killing machines—ancient, efficient, and equipped with a sensory suite beyond human comprehension. Because they strike from below, without warning. Because they live in a world we still barely understand.

But fear should not blind us to the reality and importance of sharks. They are vital, awe-inspiring creatures—worthy of respect, not demonization. Learning about their true nature may not eliminate fear entirely, but it replaces myth with knowledge—and with that, a deeper appreciation for one of the ocean’s most extraordinary beings.